S20: Bucephalus

Contents

- 1 ABSTRACT

- 2 Team Members & Responsibilities

- 3 Schedule

- 4 Parts List & Cost

- 5 Hardware Integration:- Printed Circuit Board

- 6 CAN Communication

- 7 Bridge and Sensor Controller: Bluetooth Module

- 8 Bridge and Sensor Controller: Sensors

- 9 Motor Controller

- 10 Geographical Controller

- 11 Driver Module

- 12 Mobile Application

- 13 Conclusion

ABSTRACT

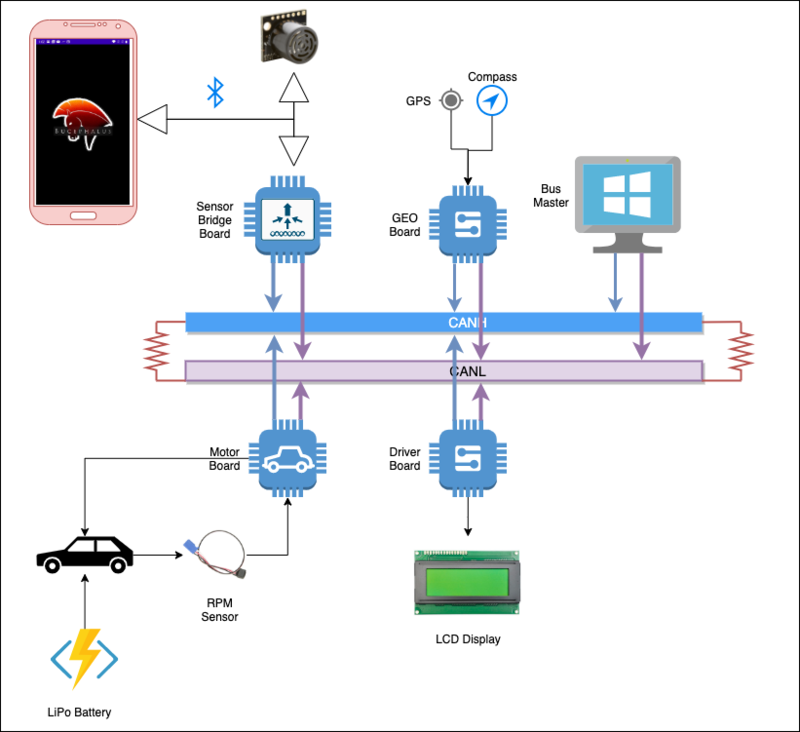

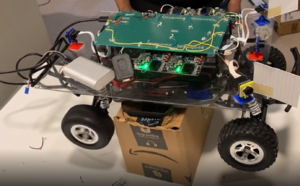

Bucephalus is a Self Driving RC car using CAN communication based on FreeRTOS(Hard RTOS). The RC car takes real time inputs and covert it into the data that can be processed to monitor and control to meet the desired requirements. In this project, we aim to design and develop a self-driving car that autonomously navigates from the current location to the destination (using Waypoint Algorithm )which is selected through an Android application and at the same time avoiding all the obstacles in the path using Obstacle avoidance algorithm . It also Increases or Decreases speed on Uphill and downhill (using PID Algorithm)as well as applies breaks at required places. The car comprises of 4 control units communicating with each other over the CAN Bus using CAN communication protocol, each having a specific functionality that helps the car to navigate to its destination successfully.

INTRODUCTION

Objectives of the RC Car:-

1) Driver Controller:- Detection and avoidance of the obstacles coming in the path of the RC car by following Obstacle detection avoidance.

2) Geographical Controller:- Getting the GPS coordinates from the Android Application and traveling to that point using Waypoint Algorithm

3) System hardware communication using PCB Design.

4) Bridge and Sensor Controller:- Communication between the Driver Board and Android Mobile Application using wireless bluetooth commmunication.

5) Motor Controller:- Control the Servo Motor for Direction and DC motor for speed. Implementation of PID Algorithm on normal road uphill and down hill to maintain speed

The project is divided into six main modules:

|

CORE MODULES OF RC CAR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Team Members & Responsibilities

<Team Picture>

Bucephalous GitLab - [1]

- Mohit Ingale GitLab LinkedIn

- Driver and LCD Controller

- Hardware Integration and PCB Designing

- Testing Team / Code Reviewers

- Shreya Patankar GitLab LinkedIn

- Geographical Controller

- Hardware Integration and PCB Designing

- Testing Team / Code Reviewers

- Wiki Page

- Nicholas Kaiser GitLab LinkedIn

- Bridge and Sensor Controller

- Wiki Page

- Hardware Integration and PCB Designing

- Hari Haran Kura GitLab LinkedIn

- Motor Controller

- Testing Team / Code Reviewers

- Hardware Integration and PCB Designing

- Abhinandan Burli GitLab LinkedIn

- Driver and LCD Controller

- Testing Team / Code Reviewers

- Hardware Integration and PCB Designing

Schedule

| Week# | Start Date | End Date | Task | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 02/16/2020 | 02/22/2020 |

|

|

| 2 | 02/23/2020 | 02/29/2020 |

|

|

| 3 | 03/01/2020 | 03/07/2020 |

|

|

| 4 | 03/08/2020 | 03/14/2020 |

|

|

| 5 | 03/15/2020 | 03/21/2020 |

|

|

| 6 | 03/22/2020 | 03/28/2020 |

|

|

| 7 | 03/29/2020 | 04/04/2020 |

|

|

| 8 | 04/05/2020 | 04/11/2020 |

|

|

| 9 | 04/12/2020 | 04/18/2020 |

|

|

| 10 | 04/19/2020 | 04/25/2020 |

|

|

| 11 | 04/26/2020 | 05/02/2020 |

|

|

| 12 | 05/03/2020 | 05/09/2020 |

|

|

| 13 | 05/10/2020 | 05/16/2020 |

|

|

| 14 | 05/17/2020 | 05/23/2020 |

|

|

Parts List & Cost

| Item# | Part Desciption | Vendor | Qty | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RC Car Chassis | Traxxas | 1 | $250.00 |

| 2 | Lithium-Ion Battery | 1 | ||

| 3 | Battery Charger | 1 | ||

| 4 | Tap Plastics Acrylic Sheet | 1 | ||

| 5 | Ultrasonic Sensors | Amazon [2] | 4 | |

| 6 | GPS Module | 1 | ||

| 7 | GPS Antenna | 1 | ||

| 8 | Compass Module | 1 | ||

| 9 | UART LCD Display | 1 | ||

| 10 | Bluetooth Module | 1 | ||

| 11 | CAN Transceivers SN65HVD230DR | 15 | Free Samples | |

| 12 | Sjtwo Board | Preet | 4 | $50.00 |

| 13 | 12" Pipe | 1 | ||

| 14 | Android Mobile Phone | 1 | ||

| 15 | Sensor Mounts | 4 |

Hardware Integration:- Printed Circuit Board

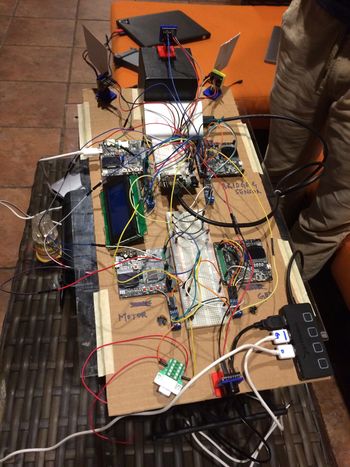

We Initially started with a very basic design of mounting all the hardware on a cardboard sheet for our first round of Integrated hardware testing.

Challenges:- The wires were an entire mess and the car could not navigate properly due to the wiring issues as all the wires were entangling and few had connectivity issues.

Hence we decided to go for a basic dot matrix Design before finalizing our final PCB Design as a Prototype board for testing if anything goes haywire.

The Prototype Board just before the actual PCB board was created on a dot matrix PCB along with all the hardware components for the Intermediate Integrated testing phase is as follows:

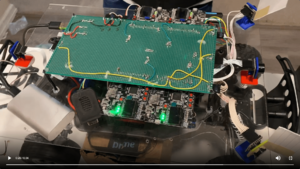

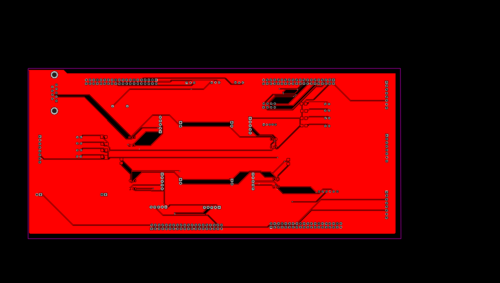

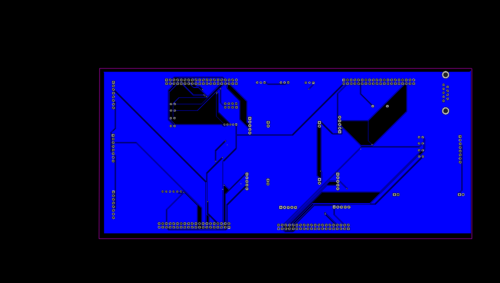

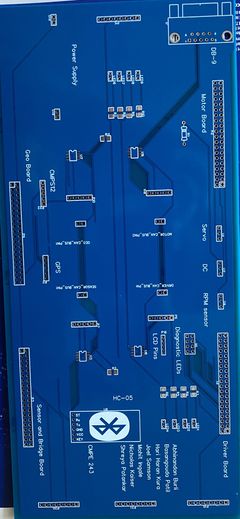

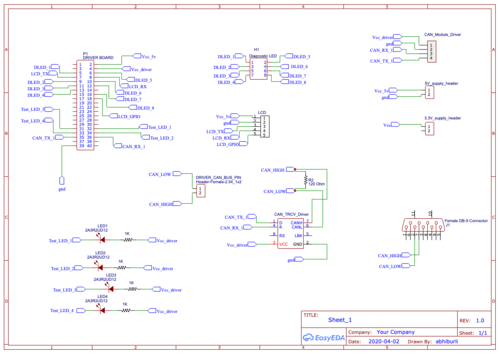

1) To avoid all the above challenges We designed the custom PCB using EasyEDA in which we implemented connections for all the controller modules(SJTwo Board LPC4078) all communicating/sending data via CAN bus. The data is sent by individual sensors to the respective controllers. GPS and Compass are connected to Geographical Controller. RPM sensor, DC and Servo Motors are connected to Motor Controller.

2) Ultrasonic are connected to Bridge and Sensor Controller. LCD is connected to Driver Controller. Bluetooth is connected to Bridge and Sensor Controller. CAN Bus is implemented using CAN Transceivers SN65HVD230 terminated by 120 Ohms; with PCAN for monitoring CAN Debug Messages and Data. Some Components need 5V while some sensors worked on 3.3V power supply. Also it was difficult to use separate USB's to power up all boards.Hence we used CorpCo breadboard power supply 3.3V/5V.

3) PCB was sent to fabrication to JLCPCB China which provided PCB with MOQ of 5 with the lead time of 1 week. We implemented 2 layers of PCB with most of the parts in top layer GPS sensor and Compass sensor. We implemented rectangular header connector for SJTwo boards, RPM sensor, DC & Servo Motor on the bottom layer. There were 2 iterations of this board.

4) Challenges :-We also need to change the header for LCD since it was having different pitch.

DESIGNING:-

AFTER DELIVERY:-

CAN Communication

<Talk about your message IDs or communication strategy, such as periodic transmission, MIA management etc.>

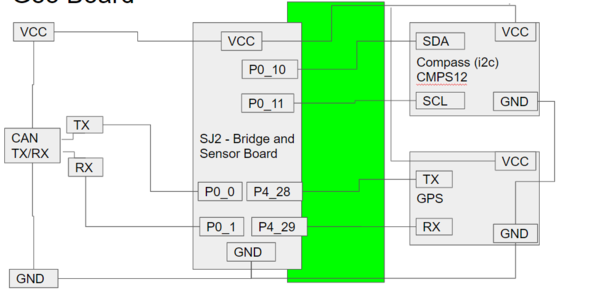

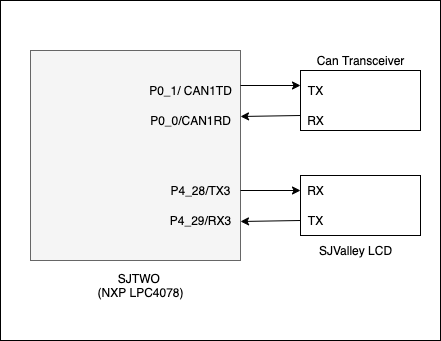

Hardware Design

<Show your CAN bus hardware design>

DBC File

VERSION ""

NS_ :

BA_

BA_DEF_

BA_DEF_DEF_

BA_DEF_DEF_REL_

BA_DEF_REL_

BA_DEF_SGTYPE_

BA_REL_

BA_SGTYPE_

BO_TX_BU_

BU_BO_REL_

BU_EV_REL_

BU_SG_REL_

CAT_

CAT_DEF_

CM_

ENVVAR_DATA_

EV_DATA_

FILTER

NS_DESC_

SGTYPE_

SGTYPE_VAL_

SG_MUL_VAL_

SIGTYPE_VALTYPE_

SIG_GROUP_

SIG_TYPE_REF_

SIG_VALTYPE_

VAL_

VAL_TABLE_

BS_:

BU_: DBG DRIVER IO MOTOR SENSOR

BO_ 100 DRIVER_HEARTBEAT: 1 DRIVER

SG_ DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd : 0|8@1+ (1,0) [0|0] "" SENSOR,MOTOR

BO_ 200 SENSOR_SONARS: 4 SENSOR

SG_ SENSOR_SONARS_left : 0|10@1+ (1,0) [0|800] "inch" DRIVER

SG_ SENSOR_SONARS_right : 10|10@1+ (1,0) [0|0] "inch" DRIVER

SG_ SENSOR_SONARS_middle : 20|10@1+ (1,0) [0|0] "inch" DRIVER

CM_ BU_ DRIVER "The driver controller driving the car";

CM_ BU_ MOTOR "The motor controller of the car";

CM_ BU_ SENSOR "The sensor controller of the car";

CM_ BO_ 100 "Sync message used to synchronize the controllers";

CM_ SG_ 100 DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd "Heartbeat command from the driver";

BA_DEF_ "BusType" STRING ;

BA_DEF_ BO_ "GenMsgCycleTime" INT 0 0;

BA_DEF_ SG_ "FieldType" STRING ;

BA_DEF_DEF_ "BusType" "CAN";

BA_DEF_DEF_ "FieldType" "";

BA_DEF_DEF_ "GenMsgCycleTime" 0;

BA_ "GenMsgCycleTime" BO_ 100 1000;

BA_ "GenMsgCycleTime" BO_ 200 50;

BA_ "FieldType" SG_ 100 DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd "DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd";

VAL_ 100 DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd 2 "DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd_REBOOT" 1 "DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd_SYNC" 0 "DRIVER_HEARTBEAT_cmd_NOOP" ;

Bridge and Sensor Controller: Bluetooth Module

Hardware Design

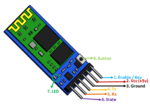

HC-05 module is an easy to use Bluetooth SPP (Serial Port Protocol) module, designed for wireless serial connection setup. It works on 2.4GHz radio transceiver frequency. The HC05 module has two operating modes - AT mode and User mode. In order to enter AT mode the manual switch on the board must be pressed for about 4 seconds. The LED display sequence on the board changes indicating successful entry to AT mode. Using AT commands various factors such as baud rate, auto-pairing, security features can be configured.

Some of the most commonly used AT commands are –

• AT+VERSION – version number of the module

• AT+ADDR – Module address. Note the slave address for paring with the master module

• AT+ROLE – 0 indicates slave module and 1 is Master module.

• AT+PSWD – To set or inquire module password

• AT+UART – Select the device baud rate from 9600,19200,38400,57600,115200,230400,460800

• AT+BIND – Bind Bluetooth address

Once the desired configurations are set, reset the module to switch back to User mode.

Hardware Features -

• Low Power Operation - 1.8 to 3.6V I/O

• UART interface with programmable baud rate

• Programmable stop and parity bits

• Auto - pairing with last connected device

Hardware pin connections can be seen in the image below.

Software Design

<List the code modules that are being called periodically.>

Technical Challenges

< List of problems and their detailed resolutions>

Bridge and Sensor Controller: Sensors

A total of four Maxbotix MaxSonar HRLV-EZ0 ultrasonic sensors are connected to the bridge and sensor controller; three in front and one in back.

<Picture>

We decided to use four ultrasonic sensors due to their relatively easy setup process, ranging capabilities, and reliability. We considered using lidar, but these sensors rely on additional factors such as lighting conditions. We specifically chose Maxbotix’s more expensive MaxSonar line because of their greater accuracy over their standard counterparts. The MaxSonar sensors have internal filtering to greatly reduce the amount of external noise affecting your sensor readings, making your readings far more reliable. The MaxSonar sensors also include an on-board temperature sensor to automatically adjust the speed of sound value based on the temperature of the environment the sensors are being used in. This means the sensor readings will stay consistent regardless of the weather and time of day (night time is much cooler than during the day).

Maxbotix offers ultrasonic sensors with different beam widths, and we chose their EZ0 sensors because they have the widest beam. Initially we thought this was a good idea because wider beams means an increased detection zone and less blind spots (width-wise). Please refer to the Technical Challenges section for details as to why we don’t recommend getting the widest possible beam for all four sensors.

<Picture (sensors only)>

Hardware Design

The ultrasonic sensors are powered using +5V, and connected to the SJtwo board’s ADC pins. There are only 3 available exclusively ADC pins on the SJtwo board, and so we changed the DAC pin to ADC mode in our ADC driver since we needed a total of 4 ADC pins. We left the RX pin of each sensor unconnected, and so each sensor ranges continuously and independently of one another. We don’t recommend doing this because the sensor beams interfere with each other when firing at the same time, but due to implementation issues, we weren’t able to use the RX pin approach. Please refer to the Technical Challenges section for details as to what problems we encountered when using the RX pin, and how we resolved the interference problems as a result of not using the RX pin.

<Insert easyEDA schematic (sensors and sjtwo board only)>

Sensor Operating Voltage

The specific sensors we chose have an operating voltage requirement of +2.5V to +5.5V. Shown below from the MaxBotix datasheets is the detection pattern based on three different operating voltages. The detection zone decreases slightly as the operating voltage is decreased.

<Ultrasonic Sensor Beam Pattern>

Additionally, the strength of the sound wave generated by the ultrasonic sensor decreases as the operating voltage decreases. A weaker sound wave means less sound “bouncing” back to the sensor, which can result in obstacles not getting detected, especially with softer surfaces like people and small plants, or thinner objects like railed gates or metal pipe handrails. We encountered this problem when using an operating voltage of 3.3V. Even though the distance the sensors could detect when powered with 3.3V was perfectly sufficient for our application, the sensors wouldn’t consistently detect softer and thinner obstacles (mainly people and thin pipes/rails). Choosing an operating voltage of 5V drastically improved the detection abilities of the sensors. The sensors consistently detected people, thin pipes sticking out of the ground, thin railed gates, metal pipe handrails, and plants that were at or above the mounting height of the sensors.

Sensor Mounts and Shields

In order to secure the sensors to the car chassis, we 3D printed sensor mounts for all four of the ultrasonic sensors. The sensor mounts are adjustable so that the nozzle of the sensor can be adjusted upward or downward. It was extremely helpful to have adjustable mounts because it took quite a bit of testing and trial and error to find the angle that the sensor nozzle needed to be tilted upward in order to detect correctly. If the sensor nozzle wasn’t pointed up high enough, the sensors would detect the road as an obstacle. We placed screws inside the mounting base hole to ensure the mount wouldn’t tilt out of position, and screwed the sensor into the mount to keep it from falling out or jiggling around. Shown below is the sensor mount design in CAD software.

<Sensor Mount in CAD Software>

Once 3D printed, the two pieces of the mount are fit together.

<Printed Sensor Mount>

In addition to sensor mounts, we put adjustable sensor shields onto the car chassis in order to prevent beam interference between the left, right, and front sensors. When all sensors are firing, sometimes one of them would detect another sensor’s beam, resulting in a false reading. Adding shields greatly reduced the occurrence of a sensor detecting another sensor’s beam, and reduced the severity to which it affected the reading.

Unfortunately, due to the Coronavirus situation we did not have access to a 3D printer and were unable to print custom designed sensor shields (the sensor mounts were 3D printed before the Coronavirus shelter-in-place happened). To make shields, we cut rectangular pieces of cardboard (yellow cardboard for aesthetics) and hot glued them each to a popsicle stick. We drilled slits into some pvc pipe and placed the popsicle stick end of the shield inside. Screws were used to tighten down the popsicle stick and keep the shield in place. The pipe pieces were hot glued to plastic bottle caps, which were then screwed into the car chassis acrylic sheet. The shields can be adjusted left or right by twisting the bottle cap screwed to the acrylic sheet, and can be adjusted up or down by pushing up or pulling down on the popsicle stick end of the shield. The adjustable sensor shields and mounts on the car chassis are shown below.

<Sensor Mounts and Shields on Car Chassis>

Placement on Chassis

All four ultrasonic sensors were placed in their mounts, and then the bottom of the mount was hot glued to the acrylic sheet mounted on the car chassis. The placement of the sensors was an important decision to make because placing them too close together or not angling the left and right sensors outward enough resulted in beam interference.

A trial and error approach was taken to find the best sensor placement configuration for the left, right, and front sensors. The sensors were taped to the edge of a desk and the readings were observed to see if the values were stable or if the beams were interfering with each other. The testing setup used to determine the best sensor placement configuration can be seen below.

<Ultrasonic Sensor Placement Testing Setup>

Through testing, it was determined that angling the left and right sensors outward at about 45 degrees, and placing them as far apart as possible on the acrylic sheet produced good results. The front and back sensors were centered on the acrylic sheet.

<Ultrasonic Sensor Placement on Acrylic Sheet>

Software Design

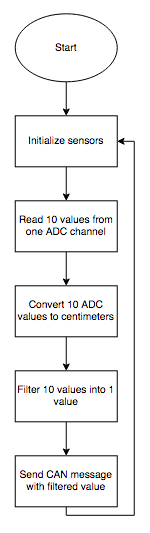

The software design of the sensor modules consisted of the following ordered steps. Initialize all sensors once the car is powered on Left sensor Read 10 values from the left sensor’s ADC channel Convert these 10 ADC values to centimeters Filter these 10 centimeter values into one filtered value Right sensor Read 10 values from the right sensor’s ADC channel Convert these 10 ADC values to centimeters Filter these 10 centimeter values into one filtered value Front sensor Read 10 values from the front sensor’s ADC channel Convert these 10 ADC values to centimeters Filter these 10 centimeter values into one filtered value Back sensor Read 10 values from the back sensor’s ADC channel Convert these 10 ADC values to centimeters Filter these 10 centimeter values into one filtered value Transmit one CAN message with four filtered values (one for each sensor)

The flowchart below is for a single sensor between the initialization step, and the send CAN message step. The three in-between steps are done a total of four times (for each sensor). To keep things clean and easy to understand, the flowchart only shows the steps for a single sensor.

Initializing the Sensors

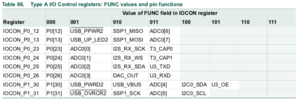

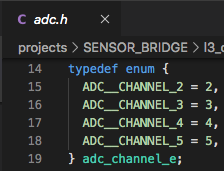

Some initialization and ADC driver modifications were required in order to get our sensors up and running. First, we wanted to use the analog out pin to receive data from all four sensors due to the simplicity of this interface. Since the Sjtwo board only has 3 available header pins with ADC functionality, we read the user manual for the LPC4058 [insert reference to user manual?] in order to see if any other available header pins had ADC capabilities. Shown below is Table 86 in the user manual, which lists all pins that have ADC functionality. Comparing this table with our SJtwo board, we found that ADC channel 3 located on P0[26] (labeled as DAC on SJtwo board) could be used as our fourth ADC pin.

We modified the existing ADC driver in order to add support for P0[26] as an ADC pin. An enumeration for ADC channel 3 was added to adc.h, and ADC channel 3 was added to the “channel check” if statement in adc.c’s adc__get_adc_value(...) function. These modifications are shown below.

In order to begin reading values from the sensors, all ADC pins must be set to “Analog Mode”. Looking at Table 85 in the LPC4058 user manual, we can see that upon reset, all ADC pins are in “Digital Mode”.

The SJtwo board’s ADC pins will not work if they are not set to “Analog Mode”, and so this code had to be added to the existing ADC driver since it was missing. We did the following IOCON register bit 7 clearing for all ADC pins inside the adc__initialize(...) function.

adc.c Modification in adc__initialize(...) <insert pic>

Once the modifications to the existing ADC driver had been made, we called adc__initialize(...) in our periodic_callbacks_initialize(...) function in order to perform the initialization of our ADC interface.

Converting to Centimeters

The raw ADC values read from each sensor aren’t inherently meaningful, and so they must be converted to centimeters in order to gauge the distance of obstacles. In order to perform the conversion, we sampled and recorded a sensor’s raw ADC values with obstacles placed at distances ranging from 0cm to 120cm in increments of 10cm. We decided to stop at 120cm because the process of collecting the sensor’s data was very time consuming and our maximum threshold value was 110cm, so there was no need to go farther. Shown below are the measurements gathered for our particular sensor model. It should be noted that the sensors produce a range of values when detecting an obstacle at a given distance, and so we averaged the values to obtain the most accurate results.

Ultrasonic Sensor Measurements <insert pic>

The values were plotted in a distance (Y-axis) versus ADC value (X-axis) graph, and a curve fit was performed in order to generate distance as a function of an ADC value. We used an application called Logger Pro because of its ability to automatically generate a curve fit for your data set.

Ultrasonic Sensor Distance vs. ADC Graph <insert pic>

We implemented the curve fit function generated by Logger Pro into code in order to convert our sensor’s ADC values to centimeters right after they were read from their respective ADC channel.

Filtering

Occasionally, the sensors will report incorrect values due to internal or external noise. Getting sensors that are more expensive usually decreases the number of times this happens, but even one incorrect reading can be a problem. For example, a sensor reading may incorrectly dip below the threshold and detect an obstacle even when there is none. Or worse, an obstacle may be within the threshold range but the sensor reading doesn’t reflect an obstacle being detected. Both of these scenarios can be avoided by filtering the sensor values before sending them to the driver controller over CAN.

The problem we were facing before filtering was the following; when setting up an obstacle in front of a sensor a certain distance away, 80cm for example, we monitored the sensor values to make sure all the readings were within a couple centimeters of 80cm. We noticed that occasionally, the output sensor readings would look something like “...80, 81, 80, 79, 82, 80, 45, 80, 78, 83, 81, 80, 79, 80…”. The sudden drop to 45 is clearly an incorrect reading because the obstacle remained at a constant 80cm away the entire time.

We considered several different filtering algorithms such as Mean, Median, Mode, and Kalman Filter. The Kalman Filter is very complex and so we didn’t feel the need to use it since other simpler options would work just as well for our application. The Mean Filter was completely out of the question because it averages the values. We want to remove the incorrect value, not incorporate it into the filtered value. The Median Filter requires the input values to be sorted in ascending order, which increases the run time and may cause us to run past our time slot in the 50Hz periodic callback function. Ultimately, we decided to use the Mode Filter because of its simplicity, short run time, and doesn’t require input values to be sorted. Choosing a filtering algorithm that has a short run time was one of the most important considerations because the sensors are running in a fast periodic callback function.

We implemented our own Mode Filter algorithm that took a number of input sensor values that have been converted to centimeters, finds the mode (most frequently occurring value) of the values, and then returns the mode as the filtered value. Through testing, we found that using an input size of 10 values to the mode filter was perfectly sufficient. A list of possible input values and the mode filter output can be seen below to better illustrate how our mode filter implementation works.

Mode Filter Output <insert pic>

A corner-case that we needed to address was the possibility of multiple modes. This case can be seen in lines 2, 3, and 5 in the table above. We chose to return the mode that was most recent in order to reflect the most recent changes in sensor values. Take line 5 for example; all values occur exactly twice, which means there are five modes. The mode returned is 69 because it is the most recent mode.

As for the actual implementation of the Mode Filter, we based it off of the Counting Sort algorithm’s “bucket storing method” with some modifications in order to make the runtime O(n), with n being the input data size (10 in our case). There is no need to sort the values for our Mode Filter, and so the sorting part of the Counting Sort algorithm is completely omitted. The idea of storing the occurence of each value in an array element number equal to the current sensor value (in centimeters) is the only idea we used from the Counting Sort algorithm. An example of how our Mode Filter works can be seen below.

Mode Filter Iterations (1) <insert pic>

Mode Filter Iterations (2) <insert pic>

The size of the array inside the Mode Filter algorithm is specifically set to 600 elements. The array needs to have element numbers for every possible sensor value (in centimeters). Our sensor values range is from 0 to 500 centimeters and so we added an extra 100 just for safety, which gives us a total of 600 array elements. This is the reason we chose to convert our sensor values to centimeters before passing them as input into the Mode Filter. If we were to pass the raw sensor values into the filter, we would need an array with around 4096 elements (SJtwo board’s ADC is 12-bit, so 2^12 = 4096).

Technical Challenges

ADC

Three main problems occurred relating to our ADC interface. First, we were unable to get the sensors to output anything besides its maximum value. We checked the voltage on the ADC pin for multiple sensors and found that instead of increasing as an object got farther away, the voltage stayed constant. We concluded that since this was happening for all the sensors we tested, it must be a problem with our initialization code. After reading the ADC section in the user manual for our SJtwo board’s processor, we realized that our ADC driver was missing one thing. For each GPIO pin being used as an ADC pin, Pin 7 of the IOCON register has to be set to “ADC Mode”. After making this change, our sensors worked like a charm.

Next, we observed that our maximum sensor values weren’t the advertised 500cm. We experimented by putting obstacles in front of a sensor at varying distances and found that 300cm was the farthest the sensor could range. After reading the user manual for our SJtwo board’s processor, we realized that its ADC module operates in reference to 3.3V. We then switched to powering our sensors with 3.3V instead of 5V, hoping to get the 500cm range as advertised. This created the problem discussed below.

Our third problem we encountered was after making the switch from powering our sensors with 5V to 3.3V. 3.3V did not supply our sensors with enough power, and so we experienced large blind spots in our detection zone, and very inconsistent sensor readings due to the sensors generating weak sound waves from a lack of sufficient power. We decided to go back to powering our sensors with 5V since 300cm was more than enough ranging capability for this project.

Inconsistent Sensor Readings

When we first started testing the sensors, we used a single sensor to make sure our connections and code initialization was correct. We placed a flat object in front of the sensor at the same distance for a very long time to see how consistent our sensor readings were. We noticed that sometimes one reading would be very low or very high compared to the other readings. After doing some research, we found that this is a very common occurrence among sensors and can be resolved by filtering. We chose to implement our own filtering algorithm, which takes in a certain number of raw sensor values, finds the mode, and returns this as the filtered sensor value.

Slow Response to Obstacles

When we first began testing obstacle detection, we used one LED for each sensor for diagnostic testing purposes. If a sensor detected an obstacle, then its corresponding LED would turn on. When the obstacle was no longer present, the LED would turn off. We noticed that the response of the LED was very slow, and the sensor values in Busmaster would not change immediately when an obstacle was present. We solved this by moving our “get sensor values” code from 10Hz to 50Hz in order to get a faster obstacle detection response.

Additionally, when we started testing our PID acceleration, we noticed that the car would not stop in time before hitting an obstacle when moving at faster speeds. We monitored the sensor values on the android app to try and troubleshoot the issue. We found that the sensor values were not changing quick enough, and so the car was crashing because it didn’t have enough time to stop. We solved this problem by removing our “light up SJtwo board’s LEDs” function from our sensor’s CAN transmit function, which was slowing down the transmission of the sensor’s CAN messages.

Detecting Obstacles when None are Present

During our initial drive testing, our car would randomly take a sharp turn or stop when there were no obstacles in range. We hooked up Busmaster to the car’s on-board PCAN dongle and walked alongside the car while it was moving in order to diagnose the issue. We saw that the sensor values were dropping below the threshold when there were no obstacles present, and even when the car was not moving. This meant that the sensors were detecting the road or even parts of the car. We resolved this by tilting the sensor heads upwards until the sensor values were at their maximum (300cm for us).

Sensor's TX/RX Pins Not Working

Our first approach to solving sensor interference issues was to fire the sensor beams one at a time, and only after the previous sensor had finished. This functionality is built into MaxBotix sensors through the TX and RX pins. If these pins are connected by following the diagrams in the sensor user manual, a sensor will fire, and then trigger the next sensor to fire once it is finished. This process will repeat continuously or only once depending upon which wiring diagram you choose in the user manual.

We followed all coding guidelines and circuitry schematics in the user manual, but our sensors would fire once, and then go into a non-responsive idle state. After almost 2 weeks of trying different configurations, wiring, and coding implementations, we decided we couldn’t waste any more time on the TX/RX pin approach and opted to solve our interference problems in a different way.

Sensor Beam Interference

The beams of our three front sensors interfered with each other, resulting in completely inaccurate sensor readings. To solve this issue, we mounted the front sensor on a platform so that it stood about 4 inches higher than the left and right sensors. We also turned the left and right sensors 45 degrees outward and added shields in order to minimize the interference from the front sensor’s beam. We found that the optimal shield placement for our setup was turning them outwards at about 22.5 degrees or less from the sensor’s head.

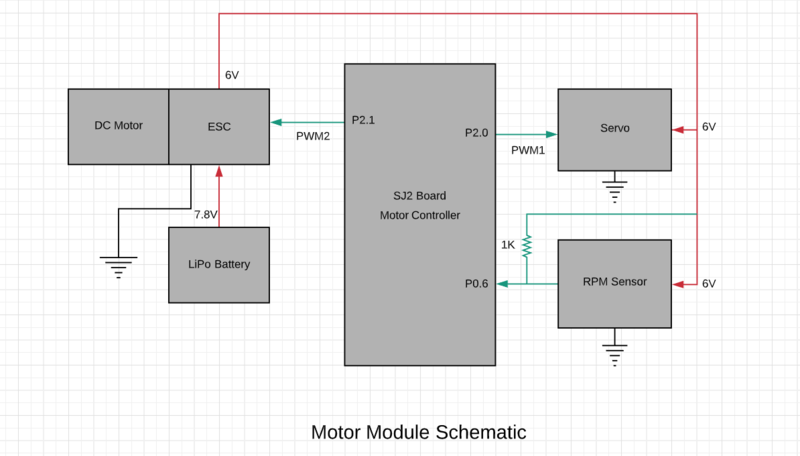

Motor Controller

The Motor Controller SJ2-Board is mainly responsible for RC-Car’s steering and speed to move the car towards the destination. The RC-Car we are using is 2 Wheel Drive which means the front wheels are used for steering which is controlled by servo motor and the rear wheels are used for car’s forward and reverse movements which are controlled by DC Motor through ESC.

Hardware Design

ESC & DC Motor

The ESC(Electronic Speed Control, Traxxas ESC XL-05) and DC Motor we used were provided with the RC car. The DC motor is controlled by ESC using PWM signals provided by the motor controller for forward and reverse movements. We used the 7.4v LiPo battery to power up the ESC. The DC motor is powered by the ESC which has a dc-to-dc converter which converts 7.4v to 6v. ESC can provide high current to the power-hungry DC motor running at faster speeds. ESC has an LED and a button which is used for calibration and setting different modes for the car.

| Wires on ESC | Description | Wire Color |

|---|---|---|

| PWM(P2.1) | Takes PWM input from SJ2-Board | WHITE |

| VDD(6V) | Power Output | RED |

| GND | Ground | BLACK |

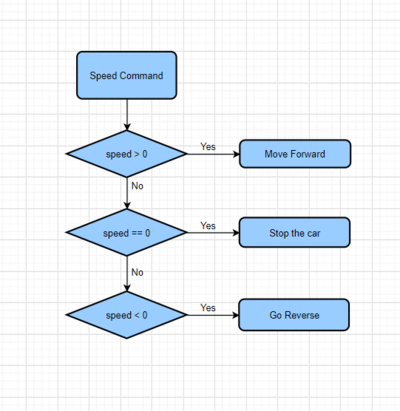

The car can be operated in the following 3 modes:

Sport mode(100% Forward, 100% Brakes, 100% Reverse)

Racing mode(100% Forward, 100% Brakes, No Reverse)

Training mode(50% Forward, 100% Brakes, 50% Reverse)

As we needed more than 50% speed for steep ramps, we used Sport mode. The frequency of the PWM signal fed to the servo motor is 100Hz. Based on the duty cycle set by the user, the car will go forward, reverse, or neutral. 10% - 20% duty cycle for reverse. 15% duty cycle for neutral. 15%-20% duty cycle for the forward motion.

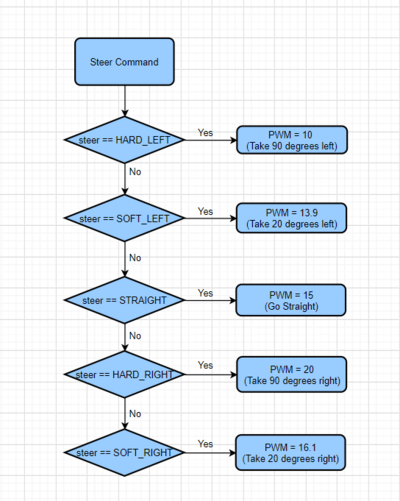

SERVO

The servo motor we used is Traxxas 2075 which was provided with the car and it is responsible for steering the car. It takes the 6V power directly from ESC. The servo motor is controlled directly from the SJ2 micro-controller board. The PWM signal fed to the servo motor is of frequency 100Hz. Based on the duty cycle of the signal sent to the servo, it rotates in the left / right direction. 10% - 20% duty cycle for left. 15% duty cycle for straight. 15%-20% duty cycle for right.

| Wires on ESC | Description | Wire Color |

|---|---|---|

| PWM(P2.0) | Takes PWM input from SJ2-Board | WHITE |

| VDD(6V) | Power Input | RED |

| GND | Ground | BLACK |

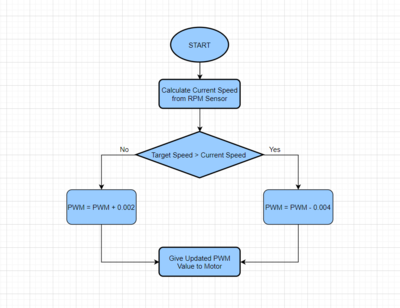

RPM SENSOR

There are two parts to the RPM sensor - one is the trigger magnet and the other is the sensor. The RPM sensor is used as an input to maintain a constant speed of the vehicle. The sensor mounts on the inside of the gear cover, the trigger magnet mounts on the DC motor shaft. The gear cover and motor shaft need to be removed using the toolkit provided along with the RC car. The procedure is similar to this video, but note that the car used in the video is a 4WD RC car by Traxxas. We made use of the trigger magnet attached to the spur gear to trigger a pulse on the sensor for every rotation of the spur gear. These pulses are then read by the SJ2 board to calculate rotations in a second and later convert it to RPM and MPH. The RPM sensor has 3 wires, the white wire is the output wire that provides the pulses to the SJ2 Board, and the other wires are Supply(6V) and GND. We also used a Pull Down 1K Resistor between Supply and RPM output wires.

| Wires on ESC | Description | Wire Color |

|---|---|---|

| GPIO(P0.6) | Provides pulses to Motor SJ2-Board | WHITE |

| VDD(6V) | Power Input | RED |

| GND | Ground | BLACK |

Software Design

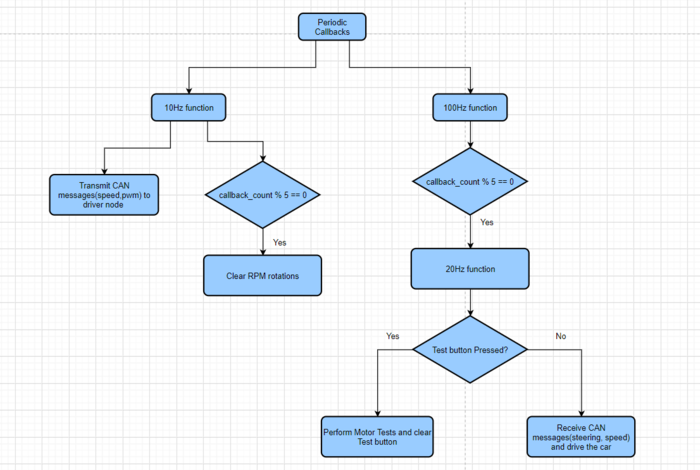

Periodic Callbacks:

Periodic Init: CAN, PWM(Servo and Motor), and Interrupts(RPM Sensor and Test button) were initialized in this function.

10Hz function: CAN messages were transmitted in this function. Also, cleared wheel interrupt rotations every 500ms.

100Hz function: Used this function to run at 20Hz. When the test button is pressed, Motor tests are performed else the car will follow driver commands.

Servo Motor:

The PWM signal fed to the servo motor is of frequency 100Hz. The motor controller receives steer controls from the driver controller and it sends corresponding PWM value to the servo motor.

DC Motor:

The PWM signal fed to the DC motor is of frequency 100Hz. The motor controller receives speed controls from the driver controller and it sends corresponding PWM value to the ESC which controls the DC motor.

RPM Sensor:

RPM Sensor gives one pulse for each wheel rotation and the software calculates speed in mph using the no. of rotations. We are re-calculating the speed, every 500ms to maintain the speed of the motor while the car is going uphill or downhill.

Technical Challenges

Car Reverse Movement

Problem: The RC car sometimes wouldn’t go reverse and this used to happen randomly.

Solution: We checked the code and were giving the correct PWM values for the car to go reverse but the car wouldn’t do it sometimes. Then, we read the ESC manual and figured out that the wheels need to stop before giving the reverse command. For us, using these Commands (FULL REVERSE and STOP) before giving reverse PWM values for the reverse movement worked well. Also, we had to use current speed in combination with these FULL REVERSE commands to make sure that these reverse commands are given only when the car is moving forward.

Car downhill movement

Problem: The car would move too fast while downhill even though the feedback loop for the speed control is reducing the PWM.

Solution: The feedback loop to maintain the speed of the car was working fine while the car was going uphill, but while downhill the car would go too fast. To resolve this, we applied brakes(FULL REVERSE commands) to the car whenever the speed crosses a certain limit.

Mounting the RPM Sensor

Problem: We had a hard time figuring out where to mount the rpm sensor, as the documentation provided by Traxxas was for 4WD and ours was a 2WD RC car.

Solution: We figured out the place to mount the sensor by chance, using common sense. It was mounted on the inside of the gear cover, where a tiny hidden place was provided.

Geographical Controller

The geographical controller is responsible for providing the required destination heading angle(destination direction) and the destination distance using compass, GPS sensors for the car to reach destination. The GPS Module which we used was MTK3339 from adafruit this gave us the current GPS co-ordinates i.e. latitude and longitude, also we used the CMPS12 compass module for obtaining the current angle of the car and heading angle of the car. Geographical module is also responsible directing the car on the shortest path to the destination using waypoint algorithm(following the checkpoints) In our design, the shortest path finding and the continuous sending of different checkpoints as car reaches each of them is checked by the geographical module. The geographic controller is also responsible for obtaining the car’s current coordinates, computing distance and angle to the next checkpoint and send these results over the CAN bus to the Driver module. The Destination latitude and longitude were sent from the android application to the bridge and sensor module using bluetooth communication and transmitted to geographical module over CAN. Upon executing the Bucephalus Android mobile application, the user was able to select a destination location, by placing a marker on the Google Map fragment. The app parsed the destination's latitude and longitude coordinates and then sent them to the bridge controller. The pathfinding algorithm (Dikstra's algorithm) is used to calculate a path to the destination based on the starting location and a series of pre-defined checkpoints comprised of longitude and latitude data.

Hardware Design

Software Design

<List the code modules that are being called periodically.>

Technical Challenges

< List of problems and their detailed resolutions>

Driver Module

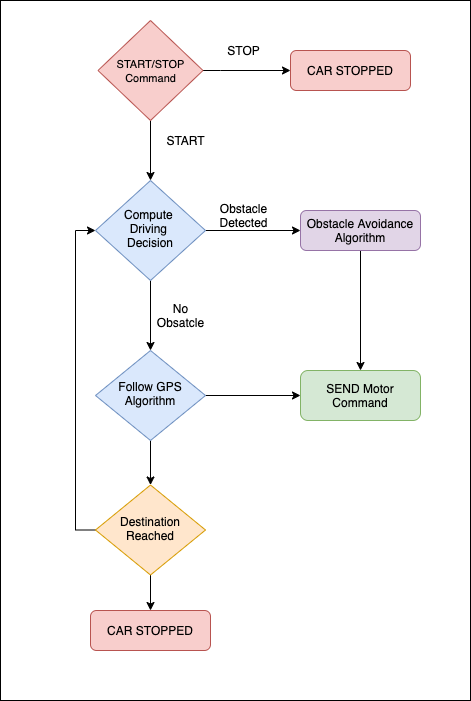

The Driver module is the brain of our autonomous car. It takes input from the Sensor and Geological controller to compute the direction of travel and sends the driving signal to the motor controller. It communicates with other modules via the CAN bus using CAN transceiver.

Hardware Design

Software Design

- The Driver control module is the brain of the Self-driving car as it takes all the critical driving decisions based on messages from the other control modules like Sensor, Geo and sends the message to the Motor control module for driving the car.

- The Driver Board receives CAN message from Geological board which includes the current heading angle of the car, destination heading angle of the car, and distance to the destination.

- The Driver Board also receives CAN message from the sensor board which includes the sensor values indicating if an obstacle is present or not. If obstacle is present the distance to the obstacle is part of the message. The values for front, left, right and back sensor is included in the message.

- The driver control board makes use of the message from the geological board and sensor board to compute the motor command for driving the car.

- The driver board has two algorithms, one which computes the motor commands based on geo controller information and other which computes the direction based on obstacle avoidance algorithm. The Obstacle avoidance algorithm has higher priority and is used if there is an obstacle detected by any of the sonar sensors. Otherwise, it makes use of the geo algorithm to compute the motor commands.

- The geo algorithm computes the deflection angle based on current and destination heading and decides on the directions of the car. The distance to the destination decides the forward movement of the car.

static float driving_algo__compute_deflection(const dbc_GEO_COMPASS_s *heading_angle) {

float deflection = heading_angle->GEO_COMPASS_desitination_heading - heading_angle->GEO_COMPASS_current_heading;

if (deflection > 180) {

deflection -= 360;

} else if (deflection < -180) {

deflection += 360;

}

return deflection;

}

static void driving_algo__get_gps_heading_direction(dbc_DRIVER_STEER_SPEED_s *driving_direction) {

float deflection = driving_algo__compute_deflection(¤t_and_destination_heading_angle);

driving_direction->DRIVER_STEER_move_speed = DRIVER_STEER_move_FORWARD_at_SPEED;

if (deflection > TOLERANCE_DIRECTION_POSITIVE) {

driving_direction->DRIVER_STEER_direction =

(deflection < 45) ? DRIVER_STEER_direction_SOFT_RIGHT : DRIVER_STEER_direction_HARD_RIGHT;

} else if (deflection < TOLERANCE_DIRECTION_NEGATIVE) {

driving_direction->DRIVER_STEER_direction =

(deflection > -45) ? DRIVER_STEER_direction_SOFT_LEFT : DRIVER_STEER_direction_HARD_LEFT;

} else {

driving_direction->DRIVER_STEER_direction = DRIVER_STEER_direction_STRAIGHT;

}

}- The obstacle avoidance algorithm first fills the data structure which maintains information if the obstacle is far, near, or very near. The algorithm then uses this information to compute direction to drive the car away from the obstacle.

typedef union {

struct obs {

uint8_t front : 2;

uint8_t back : 2;

uint8_t right : 2;

uint8_t left : 2;

} obs;

uint8_t obstacle_var;

} obstacle_s;- The Navigation and Obstacle avoidance algorithms run @20Hz, CAN messages are processed @20Hz, and debug information is sent out @1Hz.

The detailed flowcharts are shown below.

Technical Challenges

- Car Not Detecting Obstacle Fast Enough

Problem Summary: In spite of having a decent preliminary obstacle avoidance logic, the car would not stop/steer away from obstacles rather chared onto them.

Solution: After multiple testing, we observed that the speed of the car was too high for it to lose all of its momenta and come to a standstill. So we started running the car at a slower speed. Also, we added brake functionality to quickly stop the car if an obstacle is detected very near

Additonally we adjusted the threshold by calculating the distance car can travel based on time required to read the obstacle data and time required for car to take action based on the obstacle.

- Unable to get the car in reverse

Problem Summary: We were able to stop the car by sending 2 STOP commands but unable to make it go reverse.

Solution: We had to set a delay of minimum 10ms after sending the STOP and before the REVERSE command. This is how our motor understood the difference between stopping and making the motor spin in the opposite direction.

- Multiple decisions needed to be taken

Problem Summary: On the onset of each and every module, we had to always fine-tune our master logic so that it incorporated all the signals and make the system work in equilibrium. We had to incorporate start command, GPS and sensor directions which added to the decision making logic.

Solution: A robust state machine helped us to build a logically correct algorithm to incorporate every module in our system to work in order and in harmony.

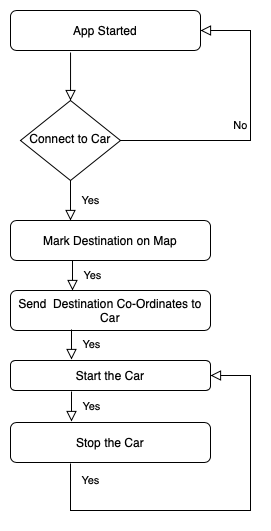

Mobile Application

<Picture and link to Gitlab>

Gitlab Link <https://gitlab.com/bucephalus/bucephalus-android-app>

Software Design

The Android Application evolved as we added one module per week as the course progressed. I started with understanding the Google Maps and how to use it in an Application, later on developed bluetooth code and finally introduced the state machine to selectively disable certain functions as to handle the bugs on a button being pressed when it was not supposed to be pressed. The implementation of the Android App was completed in a single Activity, we just had another Activity for the splash screen to display the logo.

We developed 9 revisions of the application until we arrived at the final App used for the demo.

The flowchart of the state machine used for the UI is as below-

User Interface

We kept the user interface as minimal as possible, with an extra feature of turning ON/OFF the headlights of the car. The UI had few TextFields, Google Maps and Buttons. In order to decrease minimise the use of Buttons, I decided to use the same button for Set Destination and Start by using a State Machine to change the functionality of Button.

Bluetooth

Initially we thought of using Wi-Fi for our project, but later on choose Bluetooth as suggested by the ISA team. The mobile to ecu communication is simple, but it gets complicated with ecu to mobile communication as the UI has to be updating with the latest data and the receive function should run as a Thread. We did face few challenges over here as the App would crash, it took a few trials until we arrived at the right code.

Google Map

The Google Map SDK is really huge with a lot of features, to get started we had to create an account on Google Cloud Console and enable the API and later use the API key on the Android App inside the Manifest file. One issue we faced with sending the Lat Long coordinates to the ecu was that Google Maps provides a high resolution coordinate with 10 digits after decimal points, so we trimmed it to 6 digits and we did not notice any comparable difference in the functionality of the car.

Activity Code Module

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_maps);

//View Initialization============================================================================================================

debugButton = findViewById(R.id.DebugButton);

stopButton = findViewById(R.id.StopButton);

startNdestinationButton = findViewById(R.id.Start_DestinationButton);

connecttocarButton = findViewById(R.id.ConnectButton);

listview = findViewById(R.id.listbtdevices);

headlight = findViewById(R.id.switch1);

destinationText = findViewById(R.id.destinationText);

mapFragment = (SupportMapFragment) getSupportFragmentManager()

.findFragmentById(R.id.map);

displayText = findViewById(R.id.Textview);

infoText = findViewById(R.id.infoText);

handler = new Handler(Looper.getMainLooper()) {

@Override

public void handleMessage(@NonNull Message msg) {

super.handleMessage(msg);

String speed = null, pwm = null, ch = null, dh = null, cd = null;

int state = 0;

if (msg.what == handlerState) { //if message is what we want

String readMessage = (String) msg.obj; // msg.arg1 = bytes from connect thread

recDataString.append(readMessage); //keep appending to string until ~

int endOfLineIndex = recDataString.indexOf("#");

if (endOfLineIndex > 0) { // make sure there data before ~

String dataInPrint = recDataString.substring(0, endOfLineIndex);

try {

String tokens[] = dataInPrint.split("\\s*,\\s*");

displayText.setText(" CH = " + tokens[7] + "\n" + " DH = " + tokens[8] + "\n" + " CD = " + tokens[9] + "\n");

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, e.getMessage().toString(), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

recDataString.delete(0, endOfLineIndex);

dataInPrint = " ";

recDataString.setLength(0); //MOOOOSSSSTTTTT IMPORTANT - spend entire night and including this made it work!

}

}

}

};

//MAP============================================================================================================================

mFusedLocationProviderClient = LocationServices.getFusedLocationProviderClient(this);

mapFragment.getMapAsync(this);

if(ActivityCompat.checkSelfPermission(this, Manifest.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION) == PackageManager.PERMISSION_GRANTED){

getCurrentLocation();

}else{

ActivityCompat.requestPermissions(MapsActivity.this, new String[]{Manifest.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION}, 44);

}

//BLUETOOTH======================================================================================================================

BtAdapter = BluetoothAdapter.getDefaultAdapter();

if (!BtAdapter.isEnabled()) {

BtAdapter.enable();

}

BtAdapter.startDiscovery();

/*

BondedDevicesSet = BtAdapter.getBondedDevices();

ArrayAdapter<String> arrayAdapter = new ArrayAdapter<String>(this, android.R.layout.simple_list_item_1, arrayListNameAddress);

for (BluetoothDevice bt : BondedDevicesSet) {

//this array is used for debuggin purpose and also to let the user know which device the start is sent

arrayListNameAddress.add(bt.getName() + "\n" + bt.getAddress() + "\n");

//this array has only the address to be used for connecting later on

arrayListAddress.add(bt.getAddress());

}

listview.setAdapter(arrayAdapter);

listview.setOnItemClickListener(new AdapterView.OnItemClickListener() {

@Override

public void onItemClick(AdapterView<?> parent, View view, int position, long id) {

BtServerAddress = arrayListAddress.get(position);

BtServerNameAddress = arrayListNameAddress.get(position);

BluetoothDevice Btdevice = BtAdapter.getRemoteDevice(BtServerAddress);

try{

BtSocket = Btdevice.createRfcommSocketToServiceRecord(UUID.fromString(SERVICE_ID));

BtSocket.connect();

}catch (Exception e){

//Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, e.getMessage().toString(), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

bt_failed = true;

try {

BtSocket.close();

} catch (IOException ex) {

ex.printStackTrace();

}

}

if(bt_failed == false){

displayText.setText(" connected to - " + BtServerNameAddress + "\n");

ecutomobile thread_ecutomobile = new ecutomobile();

thread_ecutomobile.start();

}

}

}

);

*/

//BUTTONS========================================================================================================================

startNdestinationButton.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {

@Override

public void onClick(View v) {

//START BUTTON

if(current_state_of_car == State.destination_sent || current_state_of_car == State.car_stopped){

try {

BtSocket.getOutputStream().write(tobesent_start.getBytes());

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

bt_failed = true;

}

if (bt_failed == false) {

infoText.setText(" sent data - " + tobesent_start);

started = true;

current_state_of_car = State.car_started;

} else {

infoText.setText(" sending data failed");

}

}

//DESTINATION BUTTON

else if(current_state_of_car == State.dest_selected){

try {

if (destination_selected == true) {

BtSocket.getOutputStream().write(tobesent_destination.getBytes());

} else {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "select destination on map", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

bt_failed = true;

}

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

bt_failed = true;

}

if (bt_failed == false) {

infoText.setText(" sent destination - " + tobesent_destination);

current_state_of_car = State.destination_sent;

} else {

}

}

}

});

stopButton.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {

@Override

public void onClick(View v) {

if (connectedtocar == true && current_state_of_car == State.car_started) {

final String tobesent_stop = "STOP";

try {

BtSocket.getOutputStream().write(tobesent_stop.getBytes());

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

bt_failed = true;

}

if (bt_failed == false) {

infoText.setText(" sent data - " + tobesent_stop);

current_state_of_car = State.car_stopped;

} else {

infoText.setText(" sending data failed");

}

}

}

});

connecttocarButton.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {

BluetoothSocket tmpSocket;

InputStream tmpIn;

OutputStream tmpOut;

BluetoothAdapter tmpAdapter = BtAdapter;

BluetoothDevice tmpDevice;

@Override

public void onClick(View v) {

if(current_state_of_car != State.app_started){

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "Already connected", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

return;

}

BtAdapter.cancelDiscovery();

displayText.setText(" trying to connect to - " + "98:D3:11:FC:1C:54" + "\n");

tmpDevice = tmpAdapter.getRemoteDevice("98:D3:11:FC:1C:54");

if (tmpAdapter.isEnabled()) {

try {

tmpSocket = tmpDevice.createRfcommSocketToServiceRecord(UUID.fromString(SERVICE_ID));

tmpSocket.connect();

} catch (Exception e) {

bt_failed = true;

if (tmpSocket != null) {

try {

tmpSocket.close();

} catch (IOException e1) {

e1.printStackTrace();

}

tmpSocket = null;

}

}

}

if (bt_failed == false) {

displayText.setText(" connected to - " + "98:D3:11:FC:1C:54" + "\n");

connectedtocar = true;

} else if (bt_failed == true) {

bt_failed = false;

displayText.setText(" trying to connect to - " + "98:D3:31:F9:5B:06" + "\n");

tmpDevice = tmpAdapter.getRemoteDevice("98:D3:31:F9:5B:06");

if (tmpAdapter.isEnabled()) {

try {

tmpSocket = tmpDevice.createRfcommSocketToServiceRecord(UUID.fromString(SERVICE_ID));

tmpSocket.connect();

} catch (Exception e) {

bt_failed = true;

if (tmpSocket != null) {

try {

tmpSocket.close();

} catch (IOException e1) {

e1.printStackTrace();

}

tmpSocket = null;

}

}

}

if (bt_failed == false) {

displayText.setText(" connected to - " + "98:D3:31:F9:5B:06" + "\n");

connectedtocar = true;

}

}

if(connectedtocar == true){

current_state_of_car = State.connected_to_car;

BtAdapter = tmpAdapter;

BtSocket = tmpSocket;

}

try {

run_thread = true;

thread_ecutomobile.start();

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, e.getMessage().toString(), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

}

});

headlight.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {

@Override

public void onClick(View v) {

if(headlight.isChecked()){

final String tobesent = "HON";

try {

BtSocket.getOutputStream().write(tobesent.getBytes());

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

}else{

final String tobesent = "HOFF";

try {

BtSocket.getOutputStream().write(tobesent.getBytes());

} catch (Exception e) {

Toast.makeText(MapsActivity.this, "is HC-05 turned on?", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

}

}

});

//STATE MACHINE TIMER============================================================================================================

Timr = new CountDownTimer(30000, 500) {

@Override

public void onTick(long millisUntilFinished) {

if(current_state_of_car == State.app_started){

infoText.setText(" 0 - connect to bucephalus ..");

startNdestinationButton.setText("SET DESTINATION");

connecttocarButton.getBackground().setColorFilter(getResources().getColor(holo_red_light), PorterDuff.Mode.MULTIPLY);

}else if(current_state_of_car == State.connected_to_car){

infoText.setText(" 1 - mark destination on the map");

connecttocarButton.getBackground().setColorFilter(getResources().getColor(holo_blue_light), PorterDuff.Mode.MULTIPLY);

}else if(current_state_of_car == State.dest_selected){

infoText.setText(" 2 - set destination to send it to car");

}else if(current_state_of_car == State.destination_sent){

infoText.setText(" 3 - start the car");

destinationText.setText(" heading to " + tobesent_destination);

startNdestinationButton.setText("START");

} else if(current_state_of_car == State.car_started){

infoText.setText(" 4 - stop button is active ..");

}else if(current_state_of_car == State.car_stopped){

infoText.setText(" 5 - car is stopped");

}

}

@Override

public void onFinish() {

start();

}

}.start();

//END============================================================================================================================

}

@Override

protected void onStop() {

super.onStop();

try {

BtSocket.close();

} catch (Exception e) {

}

}

@Override

protected void onResume() {

super.onResume();

}

class ecutomobile extends Thread {

public void run() {

// Keep looping to listen for received messages

while (true) {

if(run_thread == true){

try {

int bytes;

byte[] buffer = new byte[256];

ByteArrayInputStream input = new ByteArrayInputStream(buffer);

inputStream = BtSocket.getInputStream();

bytes = inputStream.read(buffer); //read bytes from input buffer

String readMessage = new String(buffer, 0, bytes);

// Send the obtained bytes to the UI Activity via handler

handler.obtainMessage(handlerState, bytes, -1, readMessage).sendToTarget();

} catch (Exception e) {

Log.getStackTraceString(e);

}

}else{

try {

sleep(100);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

}

}

@Override

public void onMapReady(GoogleMap googleMap) {

mMap = googleMap;

mMap.setOnMapClickListener(new GoogleMap.OnMapClickListener() {

@Override

public void onMapClick(LatLng latLng) {

int precision = (int) Math.pow(10,6);

double new_latitude = (double)((int)(precision*latLng.latitude))/precision;

double new_longitude = (double)((int)(precision*latLng.longitude))/precision;

LatLng myloc = new LatLng(latLng.latitude, latLng.longitude);

mMap.addMarker(new MarkerOptions().position(myloc).title("Destination"));

mMap.moveCamera(CameraUpdateFactory.newLatLng(myloc));

tobesent_destination = "GPS" + new_latitude + "," + new_longitude +"#";

destination_selected = true;

current_state_of_car = State.dest_selected;

}

});

}

private void getCurrentLocation() {

try{

Task<Location> task = mFusedLocationProviderClient.getLastLocation();

task.addOnSuccessListener(new OnSuccessListener<Location>() {

@Override

public void onSuccess(final Location location) {

mapFragment.getMapAsync(new OnMapReadyCallback() {

@Override

public void onMapReady(GoogleMap googleMap) {

LatLng currentLocation = new LatLng(location.getLatitude(), location.getLongitude());

MarkerOptions options = new MarkerOptions().position(currentLocation).title("bucephalus");

mMap.animateCamera(CameraUpdateFactory.newLatLngZoom(currentLocation, 17));

mMap.addMarker(options);

}

});

}

});

}catch(Exception e){

}

}

@Override

public void onRequestPermissionsResult(int requestCode, @NonNull String[] permissions, @NonNull int[] grantResults) {

super.onRequestPermissionsResult(requestCode, permissions, grantResults);

mLocationPermissionGranted = false;

switch (requestCode) {

case 44: {

// If request is cancelled, the result arrays are empty.

if (grantResults.length > 0

&& grantResults[0] == PackageManager.PERMISSION_GRANTED) {

mLocationPermissionGranted = true;

getCurrentLocation();

}

}

}

}

}Technical Challenges

We faced a few issues with the Android App as it used to crash, using better modules (Handler, Threads) solved the issue.

UI crash The UI was crashing/hanging because proper data received continuously from bluetooth had to be updated on the UI. Android provides Handler modules using which the issue was solved.

Bluetooth Code Developing the bluetooth code was a challenge as communication from ecu to mobile and mobile to ecu had to be developed. We used a Thread to develop the code, I would suggest future students develop Bluetooth code as a Service as this will help with accessing bluetooth over multiple screens and this would help in making a good UI for Debug values.

Conclusion

This project taught us how to work with so many people with same goal but different working patterns to come together and execute their ideas together in tandem to accomplish the team goal. We developed an autonomously navigating RC car. Each team member brought unique skills, passions and personalities to the project. Some team people were skilled with designing and placing components on the PCB Board, while others were skilled in firmware development, project management, catching bugs, organizing meetings etc. Some people had the ability to lighten the mood on disappointing demo days, while others had the management skill to keep the team focused and making the car its best version than the day before, while avoiding burning the team out at each other. When these different minds and their skills came together, it resulted in the final product that we all are extremely proud of, as well as one that performed well on the final demo day. The shelter in place brought more challenges in coordination as we couldn't meet much for in person meetings and everyone needed the hardware for testing their code. It was difficult for a single person who had all the hardware to always test with few members or alone and to explain others where exactly their code was failing.

It wasn't always fun and lively though. We experienced soaring highs, during few of our progress demos, where we hit almost all of our specs. We also experienced devastating lows, when we were not able to demo properly as there were coordination issues offline at the start. While we look back fondly on our project, the reality is that it was the result of 7 graduate students spending almost every day of the semester developing and fine tuning the final product. We failed and succeeded together as a team. The goal was too important. Blame fell on the team as a whole and so did success and praise. We succeeded because we failed together. We succeeded because we didn't let failure break us and instead worked harder to fine tune and improve our test cases so that no case in the testing is left unexplored and the car worked exceptionally well.

There was so much to learn. Always something new, it felt like. We developed a clean and best working PCB, to integrate all of our subsystems together with least number of wires needed and visible on the car, even though none of us had experience developing a board that complex before. We also approached new challenges such as developing an Android Mobile Application, even though none of us knew JAVA or knew Android Studio beforehand. We never stopped learning. We learned the value of investing in quality components. We honed our unit testing skills, trying to write firmware that was as high quality as our hardware. We learned about CANbus on an intimate level and applied all of the knowledge. Testing at residential area gave us a tough time especially with the GPS module and the ultrasonic sensors as the google maps did not give us the exact co-ordinates of internal society roads. while the ultrasonic sensors faced difficulty in detecting low height sidewalks.

Working on this project was a difficult yet ultimately rewarding experience. It taught us how to make use of unit tests so that we don't need hardware at all and this helped alot in online coordination with team members. We can't stress enough how important is to start the project as early as possible in the semester and to keep pushing until the final demo. Each of contributed roughly 20 hours a week to work on the project. As a result, we were exhausted by the end of it, but we also never had to pull nights sometimes to meet the deadlines. We had excellent leadership from our team lead, Mohit Ingale, as well as our mentors, Preet and ISA members Aakash, Vignesh. We also had excellent peers in CMPE 243 and are proud of what they achieved as well. Overall, we were happy to be part of this class and we hope that our project will inspire future students to develop electric vehicles.

Project Video

Project Source Code

Advise for Future Students

- FORM YOUR TEAM AS EARLY AS POSSIBLE AND START WORKING ON THE PROJECT AS EARLY AS POSSIBLE Dont't go by the team size. There is lot of work which keeps on stalking up and then can haunt us in the end of semester.

- If you are having trouble with your GPS or compass, ultrasonic(due to more obstacles at residential areas) try testing on top of one of the SJSU parking garages on a weekend. There is much less signal interference.

- Order spare parts and all parts before hand so that you don't keep running around at last moment. You will encounter defective parts and shipping wastes time and increases stress (especially nearing demo day)

- Make sure to get a power supply doesn't bun you board's fuse and supplies current less than 1A. When all the car's subsystems are running, the current draw may be higher than expected

- Don't go for cheap modules and car model from Ebay, those will probably waste more of your time and probably cost you more at the end as you might end up buying hardware again. Get quality modules and they will pay for themselves down the road.

- Make use of all the holidays specially Spring break as there are assignments from other classes too and this would be the best time when probably everyone can be free. This will save you on the final DEMO day.

- Getting access to a 3D printer can be very useful for this project, with which you can customize sensor mounts, car hood.

- Take advantage of the code reviews that Preet offers! They will fix a lot of bugs in your code and will make it a lot easier to manage each module.