S19: Run D.B.C

Contents

- 1 ABSTRACT

- 2 INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

- 3 SCHEDULE

- 4 BILL OF MATERIALS (GENERAL PARTS)

- 5 HARDWARE INTEGRATION PCB

- 6 CAN NETWORK

- 7 ANDROID MOBILE APPLICATION

- 8 BRIDGE CONTROLLER

- 9 GEOGRAPHIC CONTROLLER

- 10 MASTER CONTROLLER

- 11 MOTOR CONTROLLER

- 12 SENSOR CONTROLLER

- 13 CONCLUSION

- 14 Grading Criteria

ABSTRACT

The RUN-D.B.C project, involves the design and construction of an autonomously navigating RC car. Development of the R.C car's subsystem modules will be divided amongst and performed by seven team members. Each team member will lead or significantly contribute to the development of at least one subsystem.

INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

|

RC CAR OBJECTIVES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

TEAM OBJECTIVES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

CORE MODULES OF RC CAR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

PROJECT MANAGEMENT ADMINISTRATION ROLES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

TEAM MEMBERS & RESPONSIBILITIES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Team Members |

Administrative Roles |

Technical Roles | ||

|

|

| ||

|

| |||

|

|

| ||

|

| |||

|

| |||

|

| |||

|

| |||

SCHEDULE

|

TEAM MEETING DATES & DELIVERABLES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Week# |

Date Assigned |

Deliverables |

Status | |

| 1 | 2/16/19 |

|

| |

| 2 | 2/24/19 |

|

| |

| 3 | 3/3/19 |

|

| |

| 4 | 3/10/19 |

|

| |

| 5 | 3/17/19 |

|

| |

| 6 | 3/24/19 |

|

| |

| 7 | 3/31/19 |

|

| |

| 8 | 4/7/19 |

|

| |

| 9 | 4/14/19 |

|

| |

| 10 | 4/21/19 |

|

| |

| 11 | 4/28/19 |

|

| |

| 12 | 5/5/19 |

|

| |

| 13 | 5/12/19 |

|

| |

| 13 | 5/19/19 |

|

| |

| 14 | 5/22/19 |

|

| |

BILL OF MATERIALS (GENERAL PARTS)

|

MICRO-CONTROLLERS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL & SOURCE |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

|

| |

|

RC CAR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL & SOURCE |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

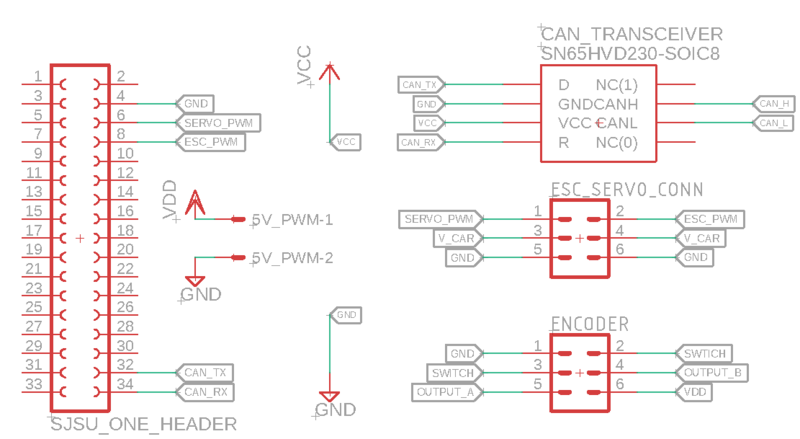

HARDWARE INTEGRATION PCB

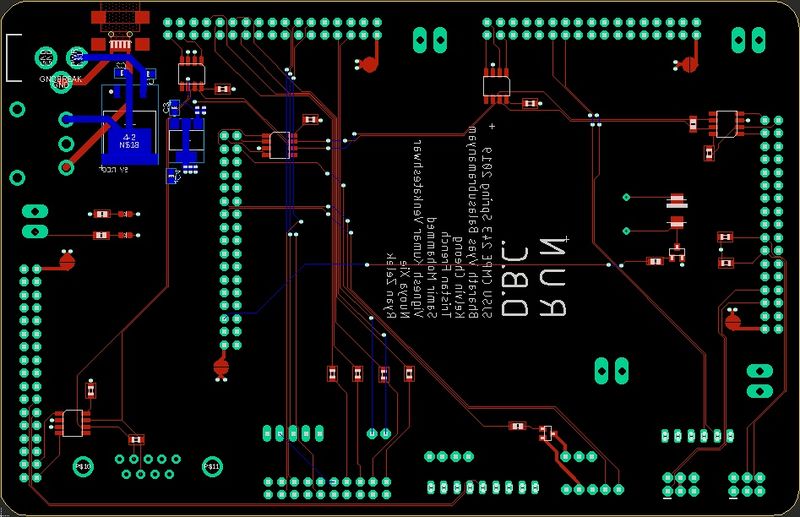

Hardware Design

The hardware integration PCB was designed with two goals:

1. Minimize the footprint of the onboard electronics

2. Minimize the chances of wires disconnecting, during drives

To accomplish these goals, all controllers were directly connected to the board's 34 pin header arrays, while all sensors were connected to the board, using ribbon cables and locking connectors. The master controller's header pins were inverted and then connected to a header array on top of the PCB, while the other controllers were mounted to the bottom. This guaranteed secure power and signal transmission paths, throughout the system.

The board consisted of 4 layers:

Signal

3.3V

5.0V

GND

Technical Challenges

Design

- Balancing priorities between HW design and getting a working prototype

- Finalizing a PCB design, when some components and module designs are not nailed down

Assembly

- DB-9 connector for CAN dongle was wired backwards in the PCB design. Because there are several unused pins, we were able to just solder jumper wires to connect CAN HI and CAN LOW to the correct pins.

- Spacing for headers with clips were not accounted for properly in the design. two of them are very close. It's a tight fit, but it should work.

- Wireless antenna connector on master board not accounted for in footprint, it may have to be removed to avoid interference with one connector.

Bill Of Materials

|

HARDWARE INTEGRATION PCB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

CAN NETWORK

<Talk about your message IDs or communication strategy, such as periodic transmission, MIA management etc.>

Hardware Design

<Show your CAN bus hardware design>

DBC File

<Gitlab link to your DBC file> <You can optionally use an inline image>

ANDROID MOBILE APPLICATION

Software Design

Development of the Android Mobile Application happened in two phases. The first involved setting up bluetooth communication between the HC-05 and the Android mobile phone, while the second involved integrating Google Maps into the application. Both phases presented unique technical challenges that we had to address.

Bluetooth Integration

Maintaining a bluetooth connection between the Android phone and the HC-05 module, proved to be more arduous that we expected. Luckily, Google provided extensive resources to help with the process, on the Android developer website (this might be the best starting point for future CMPE 243 app developers, or anyone else interested in developing an app like this.

1. Grant the phone permission to establish a bluetooth connection and access its location. We needed three to get started:

BLUETOOTH

BLUETOOTH ADMIN

ACCESS COARSE LOCATION

These permissions were included in the Application's manifest file.

Google Maps Integration

Technical Challenges

<Bullet or Headings of a module>

Bug Tracking

<Problem Summary> <Problem Resolution>

Bill Of Materials

|

ANDROID MOBILE APPLICATION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

|

| |

BRIDGE CONTROLLER

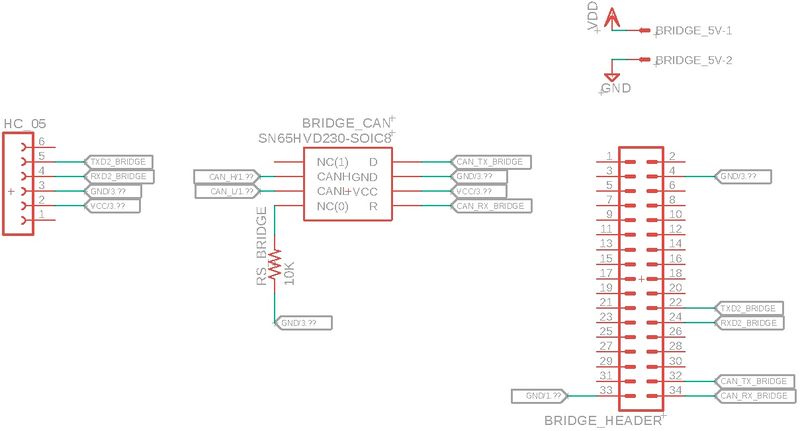

Hardware Design

The Bridge controller acted as an interface between the Android mobile phone and the car. Its main purposes were to start and stop the car wirelessly and to send destination (latitude and longitude) coordinates to the geographic controller, for use with its pathfinding algorithm.

Our approach, involved pairing an HC-05 bluetooth transceiver with the Android mobile phone and then transmitting coordinates to and from the bridge controller using UART. Checkpoints along the path-to-goal, were transmitted over CAN, to the bridge, from the geographic controller.

Upon startup, 3.3V was supplied to the HC-05.

When the user clicked the "Discover" button the app, the Android mobile phone, initiated a pair and connect sequence, with the HC-05 (using its MAC address). Upon a successful pairing, the HC-05's LED blinks slowly as opposed to a few times a second (when unpaired).

The HC-05 used UART transmit and receive queues on the SJOne board, to store data, before transmitting it to the mobile app over bluetooth.

Bridge Controller Schematic

Software Design

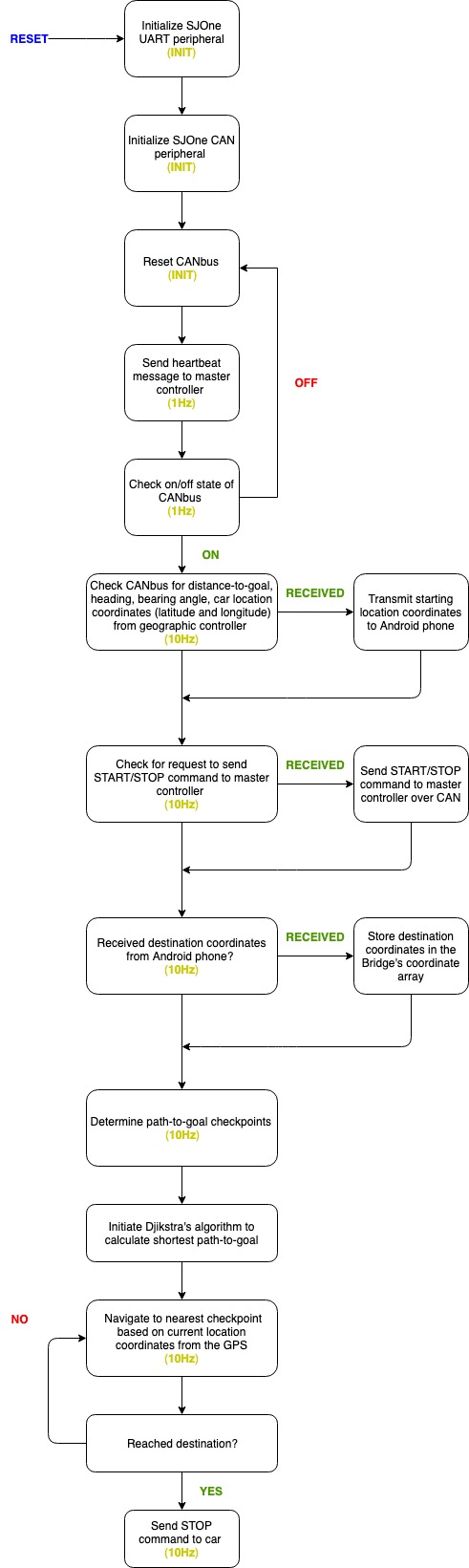

Periodic Callback: Init

Upon startup, the bridge controller initiated both its UART and CAN peripherals. In order to communicate with the Android mobile phone over bluetooth, we had to use a baud rate of 9600bps. We set our transmit and receive queue sizes to 64 bytes, respectively. We also reset the CANbus, in order to ensure proper functionality.

Periodic Callback: 1Hz

In order to verify that the Bridge Controller's CAN transceiver was operational, we sent a heartbeat message every 1Hz, to the master controller. We used an integer value '0', for simplicity. If the bridge's CAN transceiver malfunctioned, the master controller illuminated the first (onboard) LED on itself (SJOne board). This allowed us to detect MIA modules quickly, without needing to connect to the Busmaster immediately.

We also checked the status of the CANbus every 1Hz and reset the bus if it was not operational. This was to ensure that a CAN glitch would not permanently compromise the bridge controller.

Periodic Callback: 10Hz

As stated before, the Bridge Controller acted as an interface between the Android Mobile phone and the car. Therefore we needed to transmit and receive coordinates and command from the phone, as well as to/from other modules on the car.

We checked the UART receive queue for START and STOP commands from the Android mobile phone. If one was received, then a CAN message was transmitted to the Master Controller, suggesting that it either apply or terminate power to the motor. For simplicity, we sent a character, '1' for START and '0' for STOP.

We also checked for essential navigation data from the Geographic Controller and Sensor Controller. We expected the car's starting coordinates (latitude and longitude), heading, deflection angle and distance to destination from the Geographic Controller. From the Sensor Controller, we expected feedback from the front, middle and rear distance sensors, as well as the infrared sensor mounted on the back of the car. This data was stored in a UART transmit queue and then transmitted to the Android mobile phone over bluetooth, every 2Hz. The Android application displayed feedback from the Geographic and Sensor controllers below its Google Map fragment.

Technical Challenges

UART Receive While Loop

The primary technical challenge that we encountered, while developing the Bridge Controller, occurred during a demo. In an effort to display readings from sensor and geo on the Android application in real time, "CAN Receive" function was used, which in turn used a while loop to receive all CAN messages and then extract geo and sensor data, parse them and send them over UART to android application. Initially, we compiled all the data received and sent them within the CAN receive function which caused the app to crash/display junk values. To overcome this we replaced the while loop with if, however, this slowed down the rate at which messages were received and we displayed old data on App. It took a while to figure out, but we created a new function called compile and send where we concatenated data and called it at 2Hz which fixed the issue.

Bill Of Materials

|

BRIDGE CONTROLLER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

| ||

GEOGRAPHIC CONTROLLER

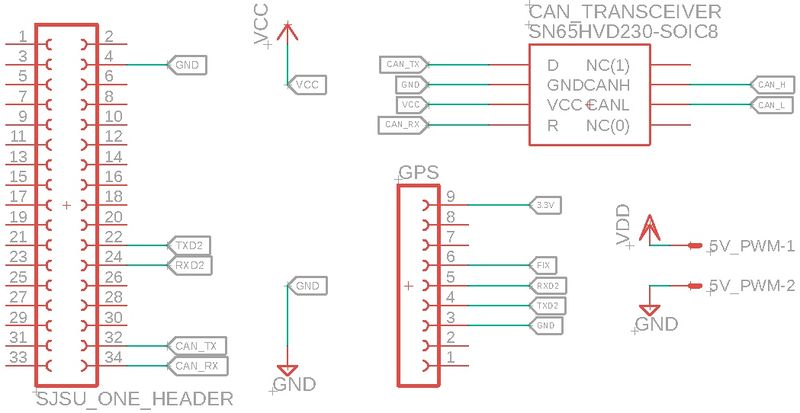

Hardware Design

The geographical controller is responsible for providing the required directions for the car to reach its destination. This is achieved using the Adafruit MTK3339 Ultimate GPS module and the CMPS14 9DOF compass module to obtain the heading, bearing, and distance to checkpoint. Geographical controller receives checkpoint from bridge module, with which the distance and deflection angle are calculated. In our design, the pathfinding and the continuous sending of different checkpoints as car reaches each of them is checked by the Bridge module. The geographic controller is only responsible for obtaining the car’s current coordinates, computing distance and angle to the next checkpoint that is provided by the Bridge module over CAN and send these results over the CAN bus.

The car's starting latitude and longitude coordinates, were calculated by the GPS and then transmitted over CAN to the bridge controller, which transmitted them to the Android phone, using bluetooth. Upon executing the RUN-D.B.C Android mobile application, the user was able to select a destination location, by placing a marker on the Google Map fragment. The app parsed the destination's latitude and longitude coordinates and then sent them to the bridge controller. The pathfinding algorithm (Dikstra's algorithm) is used to calculate a path to the destination based on the starting location and a series of pre-defined checkpoints comprised of longitude and latitude data.

Geographic Controller Schematic

GPS Module

As stated before, we used an Adafruit MTK3339 Ultimate GPS module. The GPS, along with the compass, was responsible for calculating bearing angle and distance from destination checkpoints. An external antenna was integrated, in order to help parse the GPS data more efficiently. The GPS module used UART, to communicate with the SJOne board. The baud rate for the UART interface had to be initialized twice: 9600 bps at first and then again at 57600 bps. This was because the Ultimate GPS module could only receive data at 9600 bps upon startup, but its operational baud rate was specified as 57600 bps.

The GPS module came with a GPS lock, which allowed it to use satellite feedback to parse its location. This lock was indicated by an LED, which illuminated once every 15 seconds. If no lock was found then the LED illuminated once every 1-2 seconds. The parsing of data from the GPS was in terms of NMEA sentences, each of which had a specific functionality. Out of the several NMEA sentences, $GPRMC was used. It provided essential information, such as latitude and longitude coordinates. The $GPRMC sentence is separated by commas, which the user had to parse in order to get useful data out of the module. The strtok() function was used to parse data from the GPS module, with comma(,) as the delimiter.

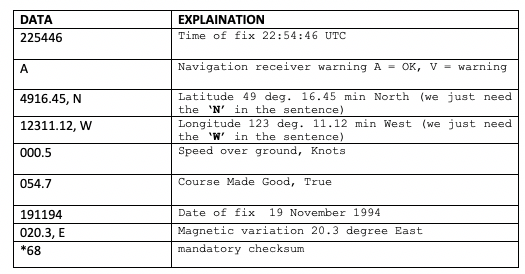

The $GPRMC sentence looks like this: $GPRMC,225446,A,4916.45,N,12311.12,W,000.5,054.7,191194,020.3,E*68

The below table explains what each of the datum in the GPRMC sentence stands for:

The first 6 fields in the NMEA sentence are the most important ones. If field 4 said ‘N’, we checked the data in field 3 which had the latitude. Likewise, if field 6 said ‘W’, we check the data in field 5 which contained the longitude. It is important to note that the longitude and latitude data are in the form degree-minute-seconds instead of true decimal. If not properly converted, they could have offset the location readings by miles.

Essential GPS Data

Bearing, Distance, and deflection angle Calculation

Bearing, calculated as an angle from true north, is the direction of the checkpoint from where the car is. The code snippet to calculate bearing is below. Lon_difference is the longitude difference between checkpoint and current location. GPS is the current location, and DEST is checkpoint location. For all trig functions used below, the longitude and latitude values have to be converted to radian. After the operations, the final bearing angle is converted to degrees and a positive value between 0 and 360.

bearing = atan2((sin(lon_difference) * cos(DEST.latitude)), ((cos(GPS.latitude) * sin(DEST.latitude)) - (sin(GPS.latitude) *

cos(DEST.latitude) * cos(lon_difference))));

bearing = (bearing * 180) / PI;

if (bearing <= 0) bearing += 360;

return bearing;

Distance between the car and the checkpoint can be calculated using GPS along. The code snippet to calculate distance is shown below. It utilizes the haversine formula to calculate the great-circle distance between two points on a sphere given their longitudes and latitudes. Like the bearing calculation, all coordinates must be in radian. The value 6371 below is earth’s radius in km.

float a = pow(sin((DEST.latitude - GPS.latitude) / 2), 2) + cos(GPS.latitude) * cos(DEST.latitude) * pow(sin((DEST.longitude - GPS.longitude) / 2), 2); float c = 2 * atan2(sqrt(a), sqrt(1 - a)); float distance = 6371 * 1000 * c; return distance;

After obtaining heading and bearing values, deflection angle, the difference in angle between your car and the checkpoint, is calculated. This is the angle value that is given to the master for steering purposes. We made that if the deflection angle is negative, the car should steer to the left. If the angle is positive, then the car should steer to the right.

deflection = gps_bearing - compass_heading; if (deflection > 180) deflection -= 360; else if (deflection < -180) deflection += 360;

Software Design

The complete flowchart for the geo module is shown below. We broke all the tasks in two iterations of the 10Hz function because if we do them in one iteration, we get the task overrun error. Therefore, the gps update rate is 5Hz.

Technical Challenges

<Bullet or Headings of a module>

Bill Of Materials

|

GEOGRAPHIC CONTROLLER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

MASTER CONTROLLER

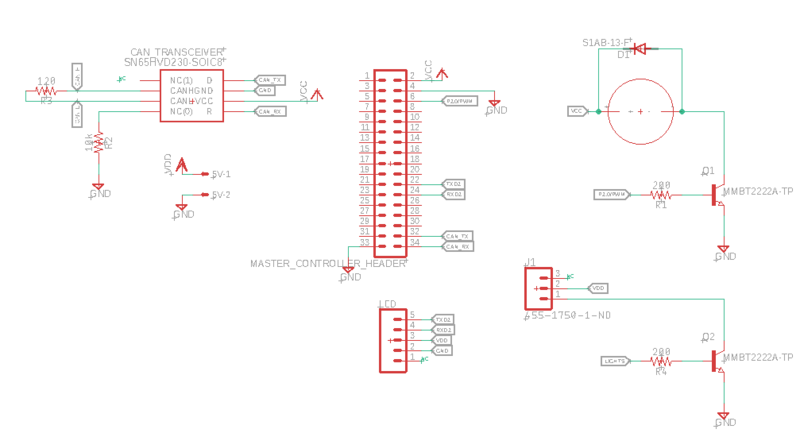

Hardware Design

The master controller is primarily interfaced with the other controllers over CAN bus. The other main interface is control of the LCD display for debug data, which communicates over UART.

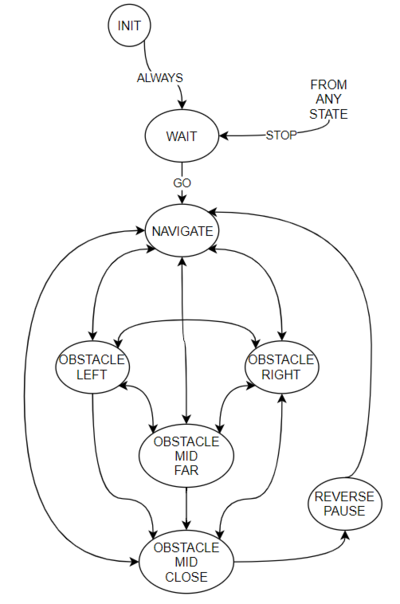

Software Design

<List the code modules that are being called periodically.>

- LCD display

- CAN read and send

- Navigation: The primary function of the master module is to process the geo and sensor data, and send steering and motor commands to the motor module.

- obstacle avoidance

- steer to checkpoint

Technical Challenges

- Quickly switching from reverse to forward "winds up" integral term of PI controller on motor module

- Solved by adding short (1 second) delay after reversing

Bug Tracking

<Problem Summary> <Problem Resolution>

Bill Of Materials

|

MASTER CONTROLLER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

|

|

| |

MOTOR CONTROLLER

Hardware Design

The motor board was responsible for both steering and spinning the wheels in order to move the car towards the target destination.

The front 2 wheels of the car handled the steering portion and it accomplished this with the utilization of the servo.

The back 2 wheels of the car handled spinning the wheels and it accomplished this through the utilization of the Electronic Speed Control (ESC) that was interfaced to the DC motor directly.

The servo was included with the RC we purchased and it was interfaced with 3 pins:

1 pin for the power supply, which was powered by the battery that came with the RC car (as opposed to the same supply that other components shared on our PCB)

1 pin for the ground signal

1 pin for the servo dedicated PWM control signal

The ESC was included with the RC we purchased and it was interfaced with 3 pins:

1 pin for the power supply (powered similar to the servo)

1 pin for the ground signal

1 pin for the ESC dedicated PWM control signal

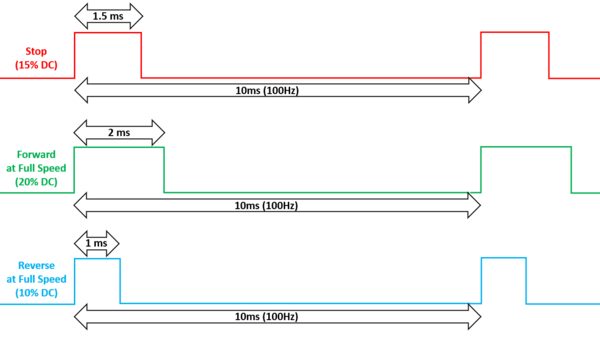

Managing the steering was relatively simple. The servo mainly requires a PWM signal in order to operate.

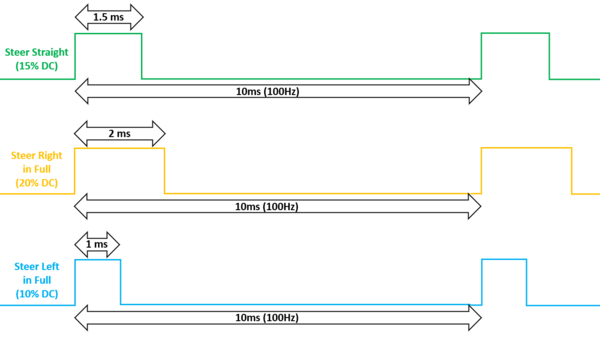

As seen through the timing diagrams below (and through experimentation), we found the frequencies and duty cycles that corresponded to actual steer left, steer right, and steer straight.

With our SJ1 board, we were able to match our frequencies and duty cycles and steer the car using the APIs that we designed.

Our code does allow for the steering to be set to any turn angle that is mechanically allowed by the car.

In order to reach the maximum turn angle setting, the programmer needs to set the PWM to either 10% (left) or 20% (right) duty cycle.

If the programmer wants a smaller turn angle, they need to program the PWM to a duty cycle that is closer to 15% (15% duty cycle means steer straight).

Managing wheel spin was a more complicated process. The ESC also requires a PWM signal in order to operate, but is not as simple as the servo's operation.

In order to reach the maximum speed in the forward direction, the programmer needs to set the PWM duty cycle to 20%.

In order to stop spinning the wheels, the programmer needs to set the PWM duty cycle to 15%.

In order to safely reverse the car, the RC car manufacturer implemented a special feature to make sure that the DC motor doesn't burn up when switching from high speed forward to going in the reverse direction.

When controlling the car with the handheld RC remote (manual control), this feature is present and the user needs to first stop and toggle some reverse commands before the car can actually move in reverse.

This means that a state machine was also needed in our code in order to enable reverse functionality.

Our software implementation of this reverse state machine is:

Stop for 100ms

Reverse for 100ms

Stop for 100ms

Reverse for 100ms

User can then reverse at any given PWM duty cycle from <15% (low speed) to 10% (full speed)

In order to maintain constant speed while moving up/down an inclined road, a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) loop is commonly used.

We didn't find the need to include the derivative component, so our speed control loop just contained the proportional and integral components.

Actual moving car speed is another component of this loop, we were able to read and calculate actual car speed through the use of an encoder.

Portions of the PID loop use constant values for the gains of each component.

Our gains were determined through a trial and error testing process.

Speed Control Timing Diagrams

Steering Control Timing Diagrams

Motor Controller Schematic

Software Design

<List the code modules that are being called periodically.>

Technical Challenges

<Bullet or Headings of a module>

- We had to change the PWM driver to hard code the sys_clock frequency. We found solution.

- Original encoder sourced is was designed to be a knob, not a motor encoder. The additional rotational resistance caused vibrations and resulted in it becoming disconnected from the motor shaft several times. The solution was to us a slightly more expensive encoder, designed for higher speed continuous operation on a motor.

Bill Of Materials

|

MOTOR CONTROLLER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

|

|

| |

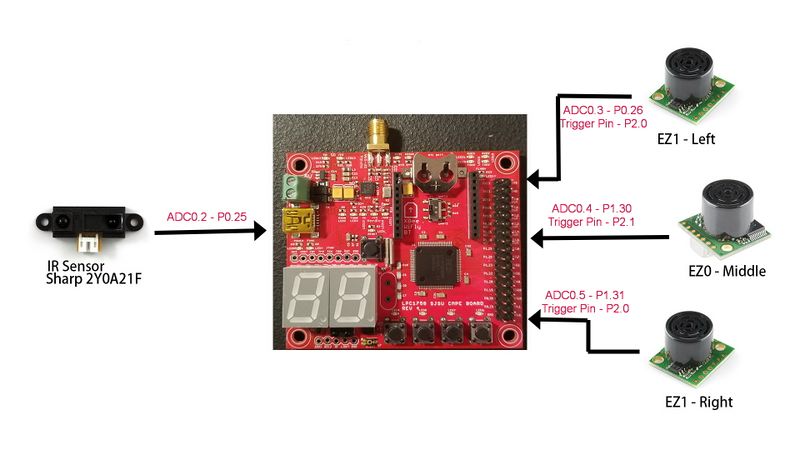

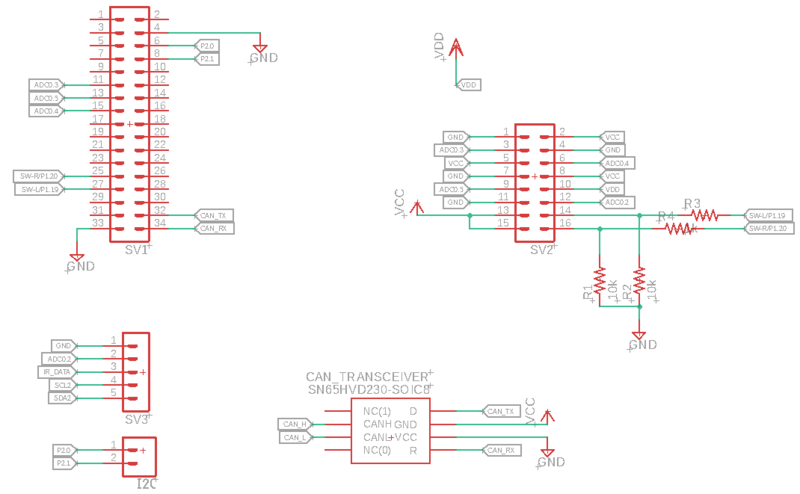

SENSOR CONTROLLER

Hardware Design

We gave a lot of thought regarding how and where sensors should be mounted to the car. In order to facilitate adjusting the directions of individual sensors, we incorporated circular grooves in the sensor bases. The hinge of the sensor mount also allowed sensors to be vertically adjusted Together with the sensor mount, this approach gave the sensor's two degrees of freedom.

Sensor Controller Schematic

CAD Design

The picture on the left shows that the hinge of the sensor guard can be adjusted to minimize the amount of interference between sensors.

The picture on the right shows the hinge of the sensor mount, allowing vertically adjustment.

Placement for the Ultrasonic Sensors

We realized that when the sensors were active, the left and right sensor ultrasonic wave output, sometimes interfered with the middle sensor, resulting in incorrect feedback. This occurred despite polling the sensors in separate periodic tasks. We discovered that, mounting the middle sensor on a higher surface than the left and right sensors decreased the interference substantially. Furthermore, by attaching two guard pieces on the left/right sensors (acting as shields), we further decreased the interference between sensors. We rigorously tested the integrity of sensor feedback with the guards in different positions, to ensure that they didn't introduce interference of their own (in certain positions).

Software Design

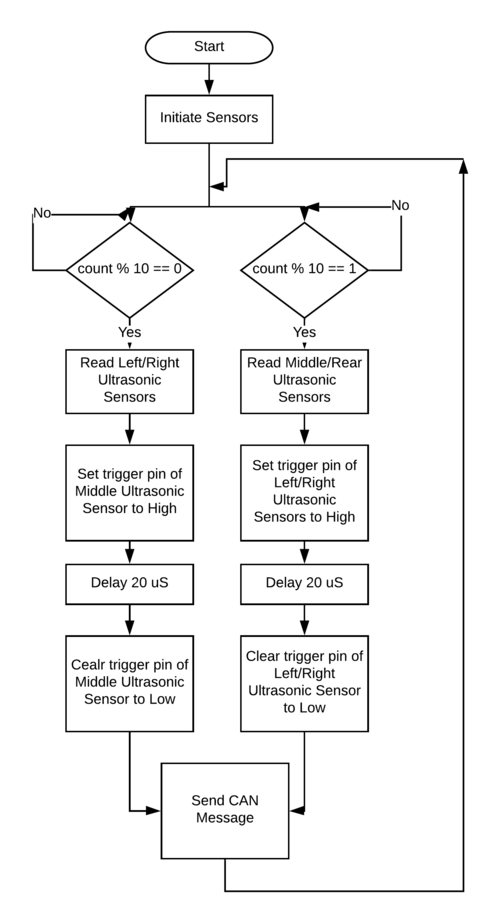

Flowchart

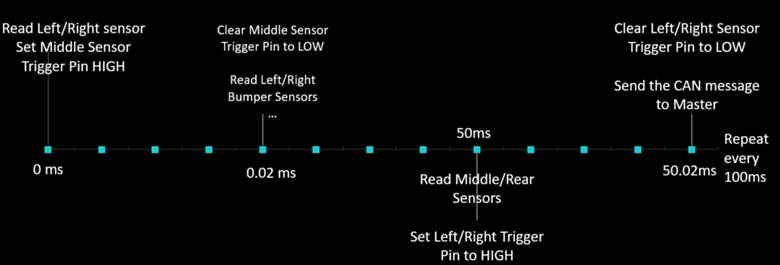

The flow diagram for sensor is shown below. We split the sensor readings to two different 10Hz tasks to minimize amount of interference between left/right and middle sensors. In one of the iterations, we read the left/right ultrasonic sensors in parallel, and immediately after reading them we trigger the middle ultrasonic sensor. Since it takes time for sound waves to bounce back from solid surface, by the time the next task begins the middle ultrasonic sensor can then read the sensor value. In the other iteration, the middle and rear sensors are read, and left/right ultrasonic sensors are triggered to output sound wave. At the end, when all information are received by the SJone board, it is send out on the CAN bus in frequency of 5Hz. It is optional to use the trigger pin (RX) to trigger the sensors to send out ultrasonic waves, but we use it because instead of letting the sensors continuously outputting ultrasonic waves and allowing them to interfere with each other, it is better to let them output waves in bursts for a much cleaner signal.

Timing Diagram

Technical Challenges

Sensor Interference

We saw a lot of interference between the front 3 sensors. We were able to overcome the issue with both hardware and software tweaks:

- Higher placement of middle ultrasonic sensor and interference guard for the left and right sensors

- Instead of leaving the RX pin of the sensors unconnected, which causes the sensors to output ultrasonic waves continuously, we toggled the RX pin, to turn off sensor ranging and only allow wave output when we needed it. The periodic callback function was also written in a way that staggered sensor triggering and reading, to allow sufficient time to process the ADC feedback.

Power Deficiency

At first, when the sensors were tested individually (as well as together on early iterations of the car), they performed to specifications. However, when other subsystems were integrated into the car, the sensor feedback fluctuated wildly. After many hours of troubleshooting, we realized that our 1A power supply was not enough to supply sufficient power to all systems on the car. We addressed the problem by using a power supply with a 3.5A output.

Unstable HR-04 Readings

At first, we used two HC-SR04 modules, as our left and right sensors. However when we tested them during obstacle avoidance we realized that their range was too narrow to reliably detect obstacles. As a result we switched to more expensive, but reliable Maxbotix EZ line of sensors.

ADC Supply Voltage

The middle sensor's also fluctuated wildly at times. After hours of testing we realized that our 5V power supply was distorting its feedback signal, due to the SJOne's ADC peripheral being powered by 3.3V. Applying a 3V power signal to the middle sensor corrected the issue.

Slow car response to obstacle due to large queue size (running average)

During our first try at obstacle avoidance we found that the car reacts very slowly to obstacles, even though the sensor update rate is 10Hz. Later we found out that the reason is because of our queue implementation. We used to have a very large queue to calculate running average. This filters out spikes but also means when an obstacle is detected it takes very long time for the running average to be updated.

Decreasing the queue size and using the median value instead of the average value solved the issue.

Bill Of Materials

|

SENSOR CONTROLLER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PART NAME |

PART MODEL |

QUANTITY |

COST PER UNIT (USD) | |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

CONCLUSION

<Organized summary of the project>

<What did you learn?>

Project Video

Project Source Code

Advice for Future Students

<Bullet points and discussion>

Grading Criteria

- How well is Software & Hardware Design described?

- How well can this report be used to reproduce this project?

- Code Quality

- Overall Report Quality:

- Software Block Diagrams

- Hardware Block Diagrams

- Schematic Quality

- Quality of technical challenges and solutions adopted.