Difference between revisions of "S13: 2D Plotter"

Matthias s13 (talk | contribs) (→Testing & Technical Challenges) |

Matthias s13 (talk | contribs) (→Stepper Motor Controller) |

||

| Line 315: | Line 315: | ||

==== Stepper Motor Controller ==== | ==== Stepper Motor Controller ==== | ||

| − | While there is a wide variety of stepper motor controllers, the one we used is shown in Illustration 12. It uses an L298 chip for motor control, and it is powered by a 5V power supply. While the controller can handle higher voltages, 5V provides sufficient power, and the chip quickly overheats when | + | While there is a wide variety of stepper motor controllers, the one we used is shown in Illustration 12. It uses an L298 chip for motor control, and it is powered by a 5V power supply. While the controller can handle higher voltages, 5V provides sufficient power, and the chip quickly overheats when using 12V. The four input controls on the stepper motor controller are connected to the outputs for each pin as shown below:<br /> |

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

Revision as of 07:45, 23 May 2013

Contents

Abstract

The following text describes the design, programming, and testing of a simple plotter. A plotter is a computer output device similar to a printer that is designed to print a design based on vectors.

This plotter was developed as the final project for the Embedded Systems Class (CmpE146) at San Jose State University, California. It consists of a wooden chassis, three stepper motors to position the print head and move the pen, and an ARM-based controller board running FreeRTOS.

To test the plotter, a simple text will be printed once the device has been completed.

Objectives & Introduction

The purpose of this project is to design a simple plotter. This plotter could then be modified to serve as a CNC router, a laser cutter, or any other vector-based 2D output device. In addition, the design of the plotter is intended as a preliminary step towards the design of a 3D printer. The experience from the design of the plotter will allow us to asses which of our current ideas can be realized with the hardware and software options available to use at the current time.

One main objective of the design is to reuse as many existing components as possible. For example, belts, gears, and motors from old inkjet printers have been collected to be used in this design.

As far as the operation of the plotter is concerned, the objectives of this project are:

- Use the ARM-based SJSU-ONE board to control all necessary hardware through GPIOs.

- Design a wooden enclosure for the hardware.

- Create a program that allows control of the hardware to create some useful output.

Team Members & Responsibilities

- Matthias

- Hardware Development

- William

- Driver Development

- Sergey

- Wiki and Documentation

Schedule

| Week | Planned Tasks | Actual Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

Parts List & Cost

| Parts | Quantity | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 SJ One Board | 1 | $65.00 |

| Nema 17 Stepper Motors | 3 | $33.20 |

| Stepper Motor Controller | 3 | $12.39 |

| Steel Rods (8mm diameter), 4 feet | 4 | $14.76 |

| Power supply | 1 | $10.00 |

| New wood (5mm thick) | 6 | $8.94 |

| Breadboard | 1 | $7.00 |

| Push Buttons | 4 | $3.96 |

| 47K Resistor | 4 | $0.50 |

| Sharpie | 1 | $1.99 |

| 4 to 16 decoder | 1 | $3.00 |

| Old wood | Various | $0.00 |

| Screws | Various | $0.00 |

| Old printer gears (various sized) | 6 | $0.00 |

| Old printer belts | 3 | $0.00 |

| Wires | Various | $0.00 |

| Gorilla Glue | 1 Tube | $4.99 |

| Total: | $166.53 |

Design & Implementation

Hardware Design

In designing the plotter, three main components need to be considered. These are the mechanical design, which consists of:

- The chassis, motors and timing belts, and the rails to position the print head on a two-dimensional grid

- The electronics to control the stepper motors and any limit switches used to ensure proper position

- The software to communicate with the hardware in order to produce the expected output.

Case and Mechnical Components

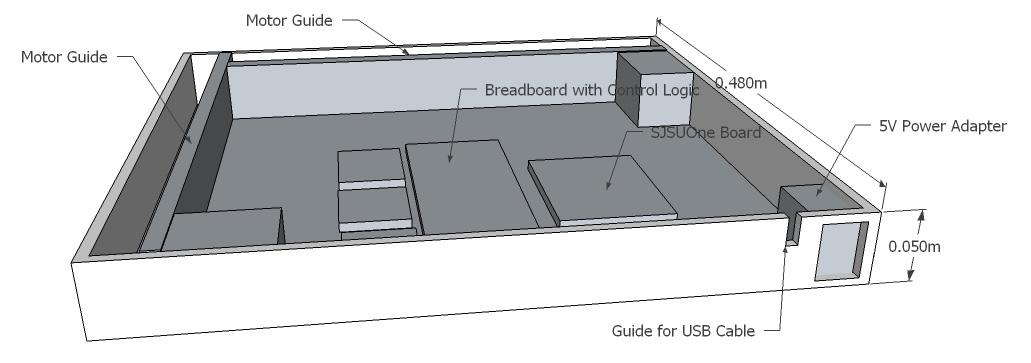

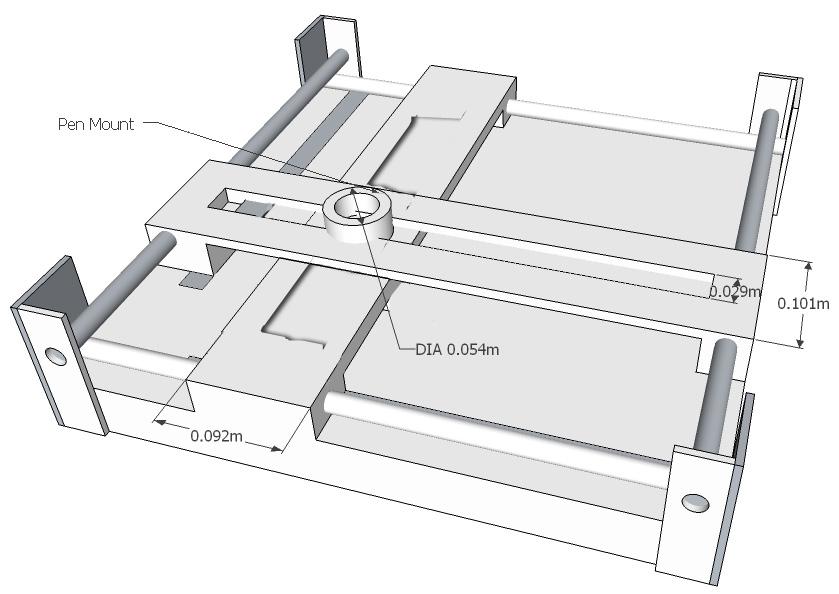

The plotter base consists of a 48 cm x 48 cm x4.5 cm enclosure (see Illustration 1) that holds the motors, the mechanical components to move the timing belts, and the electronic components.

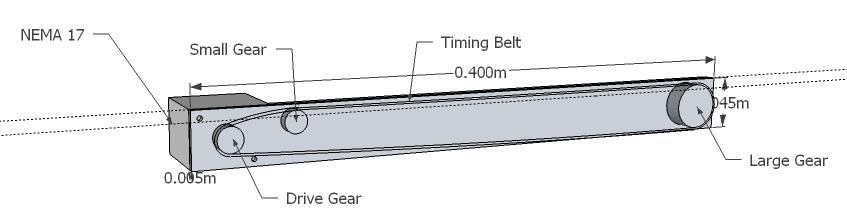

Each of the two motor guides consist of one NEMA 17 stepper motor (see Illustration 2), a large gear to hold the timing belt, and a smaller gear to position the timing belt near the top of the motor guide. To mount the motor, a large hole for the gear shaft and two small screw holes to mound the motor were drilled on one side (see Illustration 3). The gears can be attached using screws. For this particular plotter, special pins to hold plastic hears were glued into small holes. These pins were salvaged form an old inkjet printer.

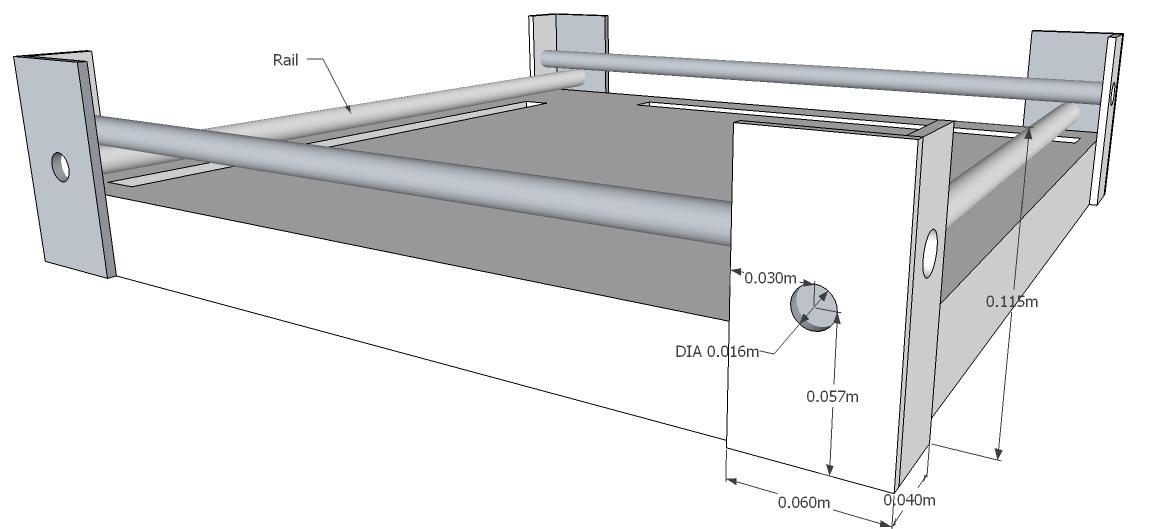

The rails to move the print head are attached to columns on the side of the printer (see Illustration 4). These rails were cut to fit from 8 mm metal bars and should be placed in parallel on opposite sides of the printer for each of the two directions. A thin opening is cut in the base where the timing belt is located. This will be the point where the two sliders are mounted to the timing belts.

The slider is currently comprised of a block of wood with a fitting guide hole. Caution should be taken that the guide block fits snugly yet can move without too much friction. Ideally, these wooden blocks would be replaced with linear ball bearings. If the rails are not completely parallel, it might be necessary to cut the guide slider on one side so that it rests loosely on the rail. This involves cutting the bottom of the slider with a saw so that the hole is turned into a half-circular groove. Illustration 5 shows an actual picture of the guide block attached to the timing belt.

Two thin wooden boards with a cut-out center are mounted crisscross on the sliders. The pen mounting mechanism is then positioned in the intersection of the two boards (see Illustration 6). It should move smoothly as the sliders are positioned in the x and the y directions. For this plotter, an empty wire-wrapping cable spool was cut in half and placed in the opening. To re-attach the two halves, a 3” strip of thin cardboard was rolled up and pushed inside the spool, holding the two pieces together.

The print head was initially designed using a large electromagnet mounted on top of a round tube. A sharpie with a metal washer glued to the top was placed underneath the magnet, and a relays circuit was designed to activate the relay. The circuit worked on the bread board, but the GPIO pin did not provide sufficient current to activate the relay, so after some failed attempts to fix the circuit, a new approach using a stepper motor was devised (see Illustrations 7). The new way was actually easier to use and more reliable.

The print head is secured in the intersection of the two rails using a small cable spool that was cut in half. An empty glue stick tube (any tube with the correct diameter will work as long as it can be cut easily) that is positioned in the middle of the spool holds the top and bottom part together. By removing the bottom, the print head assembly can be removed easily. A thin slit is cut in the side of the tube so that the rotating shaft of a motor mounted next to it will be positioned in front of the opening. A rubber band is then wound along the shaft so that it will secure a pen in place inside the tube. Moving the stepper motor clockwise or counter-clockwise will now raise or lower the pen easily.

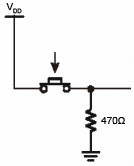

For calibration and feedback, four limit switches were added to at each end of the the two rails. The buttons were designed using a pull-down resistor (see Illustration 8), and they were wired to four GPIO pins. By reading the button status, the driver can determine if it has reached the end of a rail. The calibration information could also be used to calculate the step size by counting the number of steps from one button event to the next, and dividing the total length of the rail by the number of steps. A closeup of one limit button is shown in Image 9.

Hardware Interface

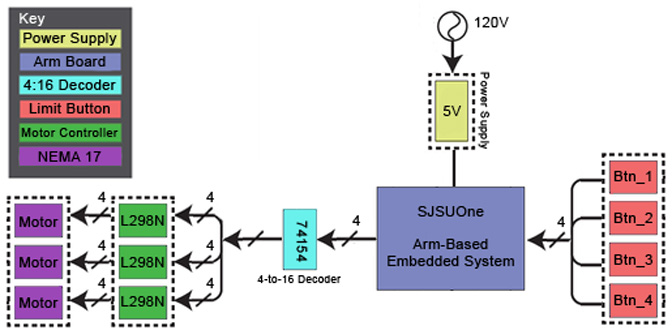

The stepper motor are controlled using two STMicroelectronics L298N Full-bridge motor drivers, which are attached to the SJSU-One ARM-based controller board (see Illustration 10).

The L298N can control a 4-wire bipolar stepper motor using a 4-bit binary input. The required sequence is 4’b0001, 4’b0010’ 4’b0100’ and 4’b1000 for clockwise operation. Reversing the inputs will produce a counter-clockwise rotation. An input of 4’b1111 or 4’b0000 will not affect the current position of the stepper motor. Therefore, it is possible to control up to four motors with a 4 of 16 decoder such as a 74LS154. We are currently using a 4-of-16 decoder and three stepper motor controllers to test the hardware performance with the z-axis motor of the 3D printer in mind. However, the current hardware only does need 2 motors.

Electronic Design

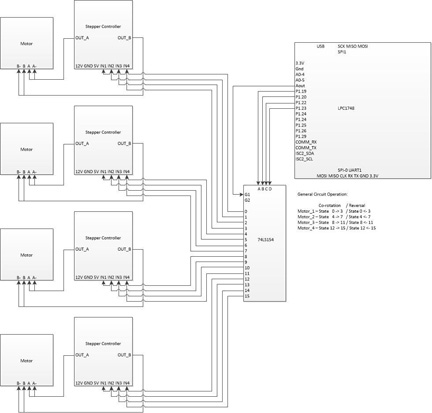

The system diagram in Illustration 11 shows the key components of the electrical system designed to control the prtinter.

Power Supply

The 5V power supply is used to power the stepper motor controllers and the microcontroller. However, during development, the system board is powered via a USB cable since the same cable is used for programming the hardware.

SJSUOne Board

The SJSUOne board is an ARM-based microcontroller running FreeRTOS. It is used to communicate with the external hardware via GPIO pins.

Limit Buttons

The limit button (Btn_1 though Btn_4) are used to provide feedback about the horizontal and vertical position of the print head. THe button is triggered when any of the two sliders has reached the end of a rail.

4-to-16 Decoder (74153)

The decoder is used to activate a particular coil in the stepper motor. A 4-to-16 decoder can control up to four motors, but it can only run one motor at a time. Each motor required 4 consecutive output pins on the decoder.

L298-Based Stepper Motor Controller

Each of the three stepper motor controllers is wired to the decoder and to one of the stepper motors. It activates a particular coil in the motor that is attached to it based on the input from the decoder. For example, 0010 activates coil 3 in motor one.

Motor

The motors used in this system are standard NEMA 17 type stepper motors common in plotters and 3D printers. This bi-polar stepper motor has 4 wires to control four coils in the motor.

Limit Switches

Each limit switch is hooked up to one GPIO input pin. In our implementation, the following pins were used:

- Button 1: P1:26

- Button 2: p1:27

- Button 3: p0:4

- Button 4: p0:5

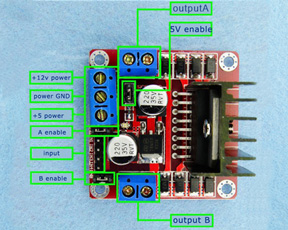

Stepper Motor Controller

While there is a wide variety of stepper motor controllers, the one we used is shown in Illustration 12. It uses an L298 chip for motor control, and it is powered by a 5V power supply. While the controller can handle higher voltages, 5V provides sufficient power, and the chip quickly overheats when using 12V. The four input controls on the stepper motor controller are connected to the outputs for each pin as shown below:

| Decoder Input | DEcoder Output Pin | Motor # | Stepper Controller Input Pin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0000 | 0 | 1 (Horizontal Control) | 1 |

| 0001 | 1 | 1 (Horizontal Control) | 2 |

| 0010 | 2 | 1 (Horizontal Control) | 3 |

| 0011 | 3 | 1 (Horizontal Control) | 4 |

| 0100 | 4 | 2 (Vertical Control) | 1 |

| 0101 | 5 | 2 (Vertical Control) | 2 |

| 0110 | 6 | 2 (Vertical Control) | 3 |

| 0111 | 7 | 2 (Vertical Control) | 4 |

| 1000 | 8 | 3 (Pen Control) | 1 |

| 1001 | 9 | 3 (Pen Control) | 2 |

| 1011 | 10 | 3 (Pen Control) | 3 |

| 1011 | 11 | 3 (Pen Control) | 4 |

The schematic for this motor setup is shown in Illustration 13.

Stepper Motor Wiring

While NEMA 17 is a standard form factor for stepper motors, not all NEMA 17 motors are wired identical. Our motors were wired as follows:

- Ground: Orange, Blue

- Coils 1,3: Red

- Coils 2,4: Yellow

To determine which wires are paired, simply test the resistance through a pair of wires.

Software Design

The software design for this project only had one task. This task had to listen to 4 customized push down buttons that limit the movement of the motors and 8 buttons on the board itself for debugging purposes while using 5 lines to drive the decoder. The decoder circuit is responsible for controlling all three stepper motors for the project.

At boot up, the head device will simply stay at it's current location, where ever it may be on the board. Once our "HELLO" code runs, the project will move the motors to the bottom left edge of the platform. Once the buttons are touched via the rails, this will tell the software that it's at the origin. The code is hardcoded to say hello. But the real magic happens in the decoder.

The decoder circuit is really simple. It counts from 0 to 3 to control the Y-axis rail, from 4 to 7 to control the X-axis, and from 8 to 11 to control the pen. It also has an enable signal to make sure none of motors are active. The software simply counts to move everything. The only huge limitation is the fact that the design can only move one motor at a time. This will be repaired with a shifting type of circuit.

Implementation

This section includes implementation, but again, not the details, just the high level. For example, you can list the steps it takes to communicate over a sensor, or the steps needed to write a page of memory onto SPI Flash. You can include sub-sections for each of your component implementation.

Testing & Technical Challenges

Testing

During development, a simple driver was created that could be used to control the motors through the push buttons on the SJSUOne board, and that did assign one direction to each push button. Once design was completed, a test pattern output routine was created that did print some predefined text. While the current output is hard-coded, the task of devising a more universal routine is trivial. This can easily be accomplished by devising an array of vector coordinates for each letter, and translating an input string to the corresponding letter array element to obtain the necessary coordinate points. Obviously, these points have to be treated as being relative to the current pen position.

Challenges

We encountered several unexpected problems during the hardware design phase. Some of the biggest problems were mechanical in nature. Some of the issues we encountered are discussed below.

Positioning of the Print Head

Moving the sliders did prove more difficult than expected. The problem was not so much a programming issue as it was caused by the mechanical properties of the design, in particular the belts used. It was difficult to find the right type of belts using recycled components, and at least one belt was too fine for the motor and the gears to properly move it. Attempts to replace the belt once the printer was completed proved very difficult since any attempt to cut and glue the belt always produced a new belt that was either too loose or too tight. We finally went with a fairly tight belt that forced us to lower the overall speed of the system to ensure that the motor has sufficient torque to move theis belt.

Print Head Design

The print head design was a problem for several reasons. For once, the general design took a while to figure out. Once that was done, the next problem was how to control the electromagnet from the SJSUOne board. Since we were unable to find a relay that worked with 3.3V, we used a NOT gate to put out the 5V to switch the relay, and utilized the 12V supply from our power supply to power the electromagnet. This worked well on a breadboard, but the circuit did not work when in conjunction with the SJSUOne board. After some tests, it was determined that the problem was most likely that the relay required a current that exceeded the current that was supplied by the GPIO pin. Instead of spending more time on this design, the print head was completely re-designed using a motor to push the pen up and down in a plastic tube.

Motor Control

The initial problem we encountered was how to control the stepper motors. Not only did we lack sufficient instructions for the salvaged motors, but we also had attempted to design the motor controller from scratch. This did proof too time consuming. We finally decided to purchase a set of NEMA 17 stepper motors, the standard motor used in most hobbyist 3D printers. We also did purchase several low-cost stepper motor controllers on eBay. However, even with the new motors, a problem was to actually create the driver since non of the instructions did appear to work since the wiring on the motors was different than what the wiring instructions expected. We finally found instructions how to easily determine the wiring of a stepper motor on the website below:

Mechanical Issues

Finding the right design to allow the sliders to move freely was probably the most challenging aspect of the hardware design. After we tried cabinet wheels and hollow metal rows, we used a block of wood with a guide hole. The secret was to keep the piece wide enough so that it does not get pulled at an angle. However, even this solution is not ideal, and we would suggest using linear ball bearings instead. Additionally, it is important to ensure that parallel rails are indeed parallel. Otherwise, the sliders will not move smoothly. We were forced to remove the bottom of the sliders to turn the hole into a half-circular groove.

Another problem was that one of the salvaged timing belts was designed for finer gear than what the motors were equipped with. This resulted in excessive slippage during operation, which could only be corrected by finding another belt and replacing the existing one. This required completely disassembling one side of the plotter. Since there was no fitting belt, a longer belt had to be cut to size and glued. A process that was not trivial.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the project proved much more difficult than we expected it to be. There were some problems with the programming part, but the biggest challenge was the mechanical aspect of the design. However, we gained several valuable insights in what not to do in our final project. For example, the decoder approach to controlling the motors does not allow us to control several motors simultaneously. This would be a problem when trying to achieve the high precision necessary for 3D printing.

Another problem was the quality of the mechanical design. The plotter project has shown that we will not be able to build a well working project like a plotter or a 3D printer using recycled parts and leftover wood. This project helped us realize that to create a good project, we need to invest in quality materials.

Interestingly, some of the biggest challenges also proved to be the most rewarding moments. In particular, the redesign of the print head taught us one valuable lesson. Sometimes stepping back and discarding a flawed approach for a completely new approach can result in a new design that is far better than the original idea. It is therefore not always a good thing to stubbornly hold on to an idea!

Project Video

SJSU - Spring, 2013 - CMPE 146 - 2D Plotter saying "HELLO"

Project Source Code

Send me your zipped source code and I will upload this to SourceForge and link it for you.

References

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Preet for continuously challenging us and showing us a large variety of different technologies that we usually do not get to explore hands-on in our lectures.

References Used

3D printing. (2013). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3D_printing

Benchoff, B. (2012). Print huge stuff with the Makerbot Replicator. Retrieved from http://hackaday.com/2012/01/09/print-huge-stuff-with-the-makerbot-replicator/

Chace, Z. (2013). 3-D Printing Is (Kind Of) A Big Deal. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2013/01/04/168627298/3-d-printing-is-kind-of-a-big-deal

Deckard, C. (1986). Method and apparatus for producing parts by selective sintering. United States. 4863538. Austin, Texas: Board of Regents, The University of Texas System

Evans, Brian. (2012). The Sciene and Art of 3D Printing. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Eveleth, R. (2012). Our three-dimensional future: how 3D printing will shape the global economy. Retrieved from http://www.smartplanet.com/blog/report/our-three-dimensional-future-how-3d-printing-will-shape-the-global-economy/559

Kelly, James F. and Hood-Daniel, P. (2011). Printing in Plastic: Build Your Own 3D Printer. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Hartmann, K. et al. (1994). Robot-Assisted Shape Deposition Manufacturing. San Diego, CA: Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation

Hotz, R. (2012). Printing Evolves: An Inkjet for Living Tissue. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390443816804578002101200151098.html

RepRap. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.reprap.org/wiki/Main_Page

RepRap Options. (2013). Retrieved from http://reprap.org/wiki/RepRap_Options

Appendix

None.